A Tangible Hope

Baylor Magazine – Summer 2017

For years, Victor Boutros, BA ’98, battled modern day slavery as a federal prosecutor for the U.S. Department of Justice, where he investigated and prosecuted international human trafficking, hate crimes and official misconduct cases around the country.

His passion for such work began growing while he was a Baylor student and intensified as a Harvard graduate school student. Boutros began traveling in the developing world, where he met many people suffering from injustices. He did not expect to find modern day slaves among the grind of poverty, hunger, homelessness and illness.

“At first, it struck me as almost unbelievable,” says Boutros. “Meeting people enslaved, who are literally being forced, compelled to work by threats of violence, was a shock.”

The International Labor Organization estimates that there are now a staggering 20.9 million victims globally.

“You almost want to change the channel because it feels so overwhelming,” Boutros says. “The sense of obliviousness: I had no idea this was happening. The sense of moral outrage: how could humans do this to each other? And then the sense of being overwhelmed: this problem seems so big; how can we ever make a dent?”

Boutros was inspired by organizations caring for survivors and wondered whether there was a way to move upstream and stop traffickers from committing their crimes in the first place. He says traffickers are committing this crime to make money, and even when survivors are rescued, the traffickers have already moved on to profit off their next victims.

“I realized that if we don’t stop the traffickers, they will keep creating more victims who need care. Trafficking begins to collapse when traffickers see that there is a hefty price tag to pay for their crimes,” says Boutros. “When traffickers discover that they could have their profits seized, lose their business, their family, their freedom, and go to jail—many begin to leave to poor alone.

“Each trafficker stopped means a future stream of victims doesn’t have to spend years enduring the trauma of human trafficking or struggling to recover from it. That’s why we are so committed to giving our lives to this work.”

“That means that lawyers and law enforcement officers have an essential role to play in this fight,” explains Boutros. “We have this huge need, all these people crying out for freedom. And we have this incredible biblical mandate, to seek justice,” Boutros says. “Yet we also have this group of lawyers and law enforcement professionals who are equipped with the very gifts necessary to help bring justice to those who are hurting.”

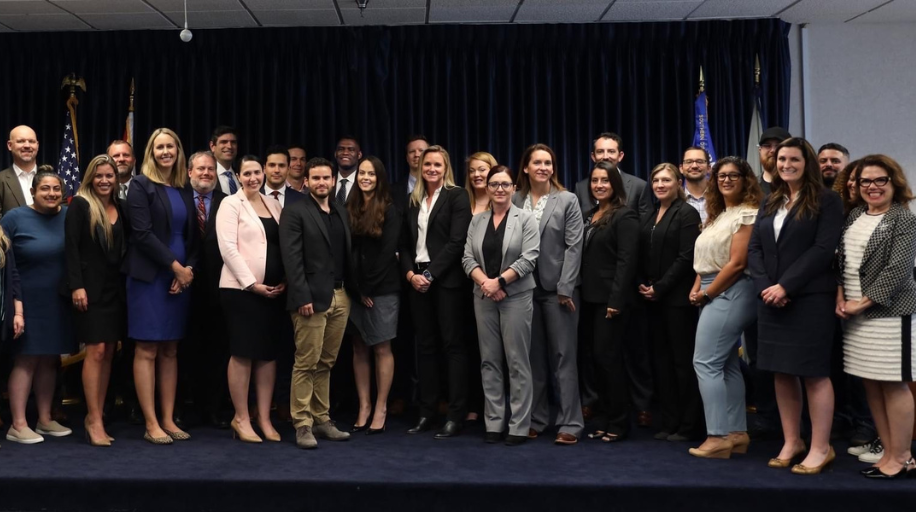

As a prosecutor, Boutros and his colleagues in the U.S. Justice Department’s Human Trafficking Prosecution Unit realized the need for more trafficking cases to be tried across the nation. With leadership and support from the Human Trafficking Prosecution Unit, the U.S. Departments of Justice, Homeland Security and Labor announced the creation of the Anti-Trafficking Coordination Teams (ACTeams), piloted in six federal districts. A team of federal agents and prosecutors was tapped to focus on human trafficking enforcement in its district, receive specialized training, and then partner with the Human Trafficking Prosecution Unit to prosecute cases.

Over a two-year period, the ACTeams had tremendous impact within these six districts, which saw a 114 percent increase in trafficking indictments, compared to only 12 percent in the other 88 districts. The six districts also had more convictions than the other 88 federal districts combined.

“Honestly, it wasn’t rocket science; we just applied the tried-and-true formula for how we build specialized skills in any area, which is mastering the core knowledge that you need to be effective and building skills with others in the field who have done this before,” Boutros explains.

According to the International Labor Organization, approximately 93 percent of slavery occurs in developing countries. So, Boutros set out to find a way he could make the biggest impact. He left the Justice Department to found the Human Trafficking Institute (traffickinginstitute.org) with fellow human trafficking prosecutor John Richmond, to bring the proven model to developing countries serious about improving their trafficking enforcement.

Although the motives of some developing country leaders may be based in part on self-interest, factoring in their economic incentives to tackle trafficking problems makes Boutros’s battle much less daunting.

“Attempting to change the moral landscape of an entire country feels impossible, but now there are more countries who see their trafficking problems as an obstacle to achieving their economic objectives. For example, under U.S. law, a poor ranking on the State Department’s annual Trafficking in Persons Report can impact its economic relationship with the United States. Some countries are also worried about losing out on investment from multinational companies concerned about trafficking in their supply chains,” Boutros explains.

Nonetheless, a huge problem in enforcement exists because of untrained police and prosecutors with no human trafficking enforcement experience. Human trafficking is illegal in every country, but trafficking explodes where the laws are not enforced.

“What we’ve discovered is that in parts of the developing world, 85 percent of the police force get zero training in criminal investigation,” Boutros says. “To ask them to do a proactive human trafficking investigation is like asking you or me to go out and do surgery.”

Boutros says the next step is equipping these law enforcement agents and prosecutors with necessary skills.

“Only then can they begin to respond to the directives coming down the chain of command and create that little bit of enforcement that causes big drops in the prevalence of trafficking,” he says.

The Human Trafficking Institute is filling the training void by connecting law enforcement, prosecutors and judges who have experience working trafficking cases with their counterparts who prefer to be trained by people in their same disciplines.

Boutros’ use of an effective, systematic approach means real change is happening. Millions of people in hopeless situations now have reason to believe, no matter where they are in the world. He says a trafficker’s decision to enslave people often boils down, not to a moral or spiritual decision, but to a simple cost/benefit analysis of using forced labor or paying workers.

“Right now, traffickers in developing countries are not afraid. In places like India, you’re literally more likely to be struck by lightning than go to jail for openly owning a slave. Many traffickers who own businesses like hotels, restaurants, brick kilns and rock quarries are only willing to use forced labor because they know there’s no chance that they will get in trouble for it,” says Boutros.

“We have compassion for trafficking victims, but it’s hard to draw near to those in pain with our time, energy and resources if we don’t really believe that anything can change.”

Boutros asserts that with the right investment of resources, specialized units of police and prosecutors with the skills and tools to conduct raids, free victims and stop traffickers will measurably decimate the prevalence of trafficking.

“But I think the real front lines of the battle against trafficking are on the battleground of hope—real, tangible hope,” Boutros explains. “We have compassion for trafficking victims, but it’s hard to draw near to those in pain with our time, energy and resources if we don’t really believe that anything can change.

“What we have discovered through our years of work in this field is that things can change,” he says. “Whole communities can begin to be safe and free, and it doesn’t require prosecuting all the traffickers. Once vetted law enforcement teams are equipped with the skills and tools to put traffickers behind bars, many traffickers begin to see their crimes as too risky. Each trafficker stopped means a future stream of victims doesn’t have to spend years enduring the trauma of human trafficking or struggling to recover from it. That’s why we are so committed to giving our lives to this work.”

Boutros, who was recognized as the 2015 Baylor University Young Alumnus of the Year, holds advanced degrees from Harvard, Oxford and University of Chicago School of Law. He co-authored The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence, with Gary Haugen, for which they received the Grawemeyer Award for Ideas Improving World Order.