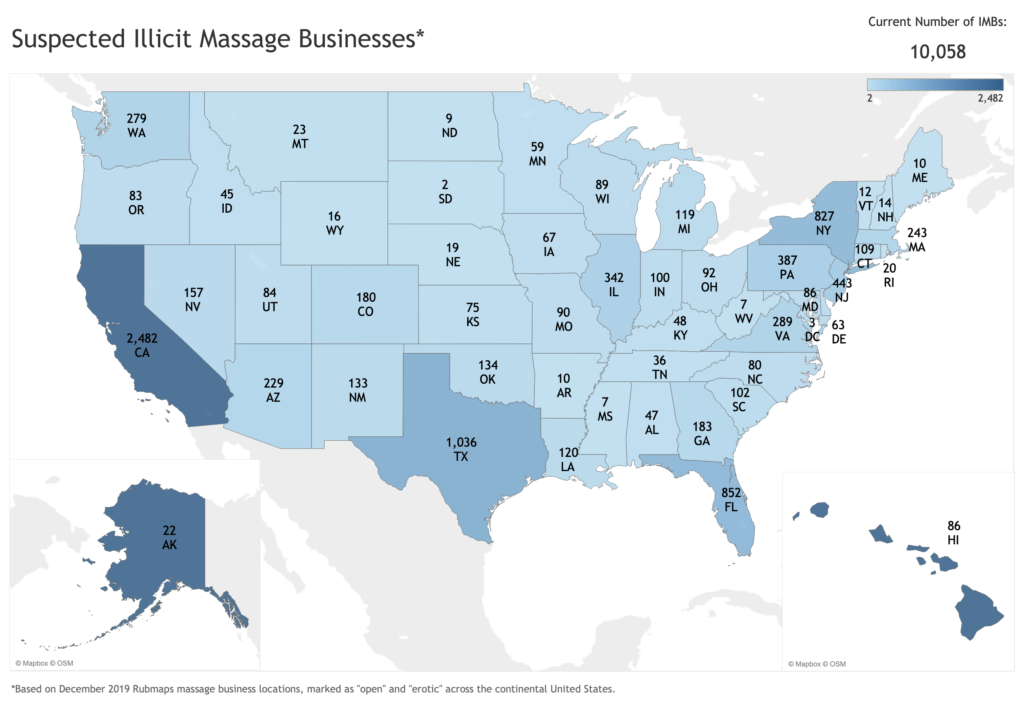

In every state in the United States1, more than 9,0002 suspected Illicit Massage Businesses (IMBs) purportedly exploit tens of thousands of women, profiting from their labor and commercial sex services. Well-documented cases3 bear out an appallingly common story of exploitation for the profit of others:

- Victim workers, typically women aged 30 to 50 from China, Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam, arrive legally in the United States on visitor H1B or H2B visas, often driven by the pursuit of economic need and opportunity for themselves and their families.4 These workers often learn of a potential job opportunity through fraudulent recruitment ads on social media platforms such as WeChat and KaKao Talk.5

- After arriving in the United States, usually following a route through JFK or LAX airports, workers begin their employment at massage businesses, typically providing sexual services6, 7 that are advertised to sex buyers through sites such as Rubmaps.com.8

- Due to the costs of obtaining travel brokers to assist with the visa process and travel arrangements, workers now find themselves with an exorbitant debt to repay, in the tens of thousands of dollars—often upwards of $50,000.9

- Victim workers then spend years moving “to different cities and states,”10 cycling in and out of IMBs, where they often sleep onsite11 and are expected to perform sexual services for an average of 6 to 10 customers per day (and often higher numbers of customers in many cities).12 In exchange, they receive payment toward their debt, which includes but is not limited to, the costs of their transport to the United States, lodging (in said business, often under surveillance), food, etc.13

- The cycle repeats. Women continue to be transported as though they are commodities throughout the vast and sophisticated network of IMBs. They are often compelled into labor or sexual services.14 Their exploitation generates an estimated $2.8 billion in annual revenue in the United States15 for business owners and operators who operate largely with impunity in American cities.

This scenario plays out on a daily basis in communities where the vast majority of IMBs thrive in plain sight.16, 17 As observed by researchers Sean M. Crotty and Vanessa Bouché in their 2018 study of IMB locations in Houston, “The traditional understanding of a red-light district, occupying a few blocks of an area of urban disinvestment, is insufficient for describing the primary zone of IMB concentration…Indeed, it appears that the commercial sex trade is not an aberration within the retail landscape of Houston, but rather a foundational component of that landscape.”18

In recent years, awareness of the issue has increased substantially along with targeted response efforts by law enforcement, service providers and anti-human trafficking task forces and coalitions. As efforts to increase awareness and combat human trafficking in the United States trend in a generally positive direction19, the sheer pervasiveness and persistence of the Illicit Massage Industry (IMI) presents two questions:

- Why is the illicit massage industry (IMI) thriving?

- How can communities across the United States more effectively and sustainably combat the large-scale labor exploitation and sex trafficking inside the Illicit Massage Industry?

To answer the first question, it is important to understand what an Illicit Massage Business (IMB) is and what it is not.

It is critical to make a distinction between legitimate, registered businesses and fronts for labor and sex exploitation. The vast majority of massage businesses fall into the former category. These are licensed therapeutic and relaxation massage establishments – legitimate, reputable businesses. They operate legally and provide relaxation and therapeutic non-sexual massage services to clientele in communities of all sizes.

In contrast to legal, licensed massage businesses, Polaris states, “’illicit massage business…describe(s) a very specific type of exploitative, organized, commercial-front trafficking venue…implicated over and over in cases reported to the [National Human Trafficking] Hotline.”

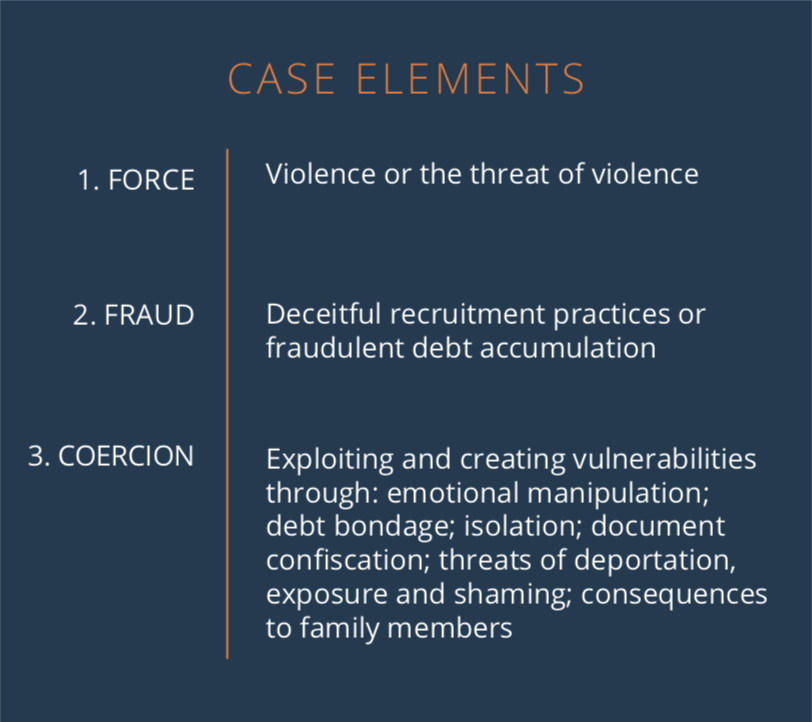

To be considered human trafficking in any venue, a situation must include20:

The American Massage Therapy Association observes, “perpetrators have used the guise of operating a massage therapy business to carry out their crimes…”. This “guise of legitimacy” is what makes the crime of human trafficking in the Illicit Massage Industry (IMI) so successful. Researchers and investigators have found that the perpetrators driving the IMI are not one-off bad actors. Rather, the perpetrators driving the IMI are large-scale, well-organized criminal networks more akin to the mafia, operating “massage” business operations as fronts for providing sexual services. Investigative journalists note these operations are “built to survive police raids.”21

Bob Houston, President and Co-Founder of Praesidium Partners (changing to Heyrick Research in 2020), a Washington, D.C.-based organization combating the illicit massage industry, spent 27 years with the FBI specializing in counterterrorism and transnational organized crime. He identifies the IMI as a criminal enterprise that fits squarely within the transnational organized crime framework.

“To qualify as a transnational organized crime network, an enterprise’s activities need to be self-perpetuating, structured, coordinated, and occur across national borders. The illicit massage industry meets these requirements. Such a network generates illicit revenues which are hidden from taxing authorities, using corruption and violence as business tools,” Houston said.

This criminal enterprise is replete with the factors that allow for a thriving industry to profit from widescale commercial sexual exploitation and labor exploitation of women. Some examples include:

- Robust supply chains that exploit U.S. visa processes22

- Exhaustive methods of controlling victim workers (described below)

- Exploitation of gaps in state and local regulatory and ordinance structures

- An inexhaustible market demand from sex buyers who often face limited consequences for purchasing illicit sex23

- Extensive money laundering to ensure high-margin profits for a largely untaxed industry24

Below is a list of factors IMI trafficking networks exploit to operate a robust global sex trafficking industry:

Business Drivers of the Illicit Massage Industry: Exploitation of Systemic Vulnerabilities

In the United States, evidence abounds to indicate the IMI thrives largely with impunity because IMB operators exploit vulnerabilities in regulatory, enforcement and nonimmigrant visa processes and systems, as well as the vulnerabilities of workers themselves. In particular, IMI network operators utilize the following approaches to operate IMBs successfully in the United States:

- The veneer of legitimate storefronts and accompanying business registration provide cover and reduce real and perceived risk for sex buyers. The vast majority of IMBs are “hidden in plain sight” inside strip malls or community business districts as well as single family homes in un-zoned or dual-zoned commercial-residential areas.25 A 2018 research paper examining IMBs in Houston, Texas, stated: “IMBs operate as traditional brick-and-mortar retail establishments. The only distinction between an IMB and a legal personal health services retailer like Massage Envy is that the services available include sex acts rather than therapeutic or medical rehabilitation massage.”26

In March 2019, The New York Times observed,

“The ubiquity of massage parlors offers an accessibility and sheen of normalcy not offered by traditional brothels. And as the massage parlors have expanded even into small-town America in recent years, meticulously detailed review sites like Rubmaps have served as the Yelp and Foursquare of the illicit parlor business, with graphic anatomical descriptions of the women and explicit breakdowns of the sexual services proffered.”27

- IMB operators exploit gaps in city, state, and municipal codes governing business operations. Illicit massage businesses often possess a “clean” paper trail of business records and utilize legitimate financial institutions for money laundering purposes. Houston notes that these enterprises,

“like other businesses, function using a division of labor and delegation of responsibilities. In the IMI, a person or company owns one or more IMBs. There are paper owners and beneficial owners, the former often being someone paid to lend their ‘clean’ name to business records and the latter an actual owner who profits from the enterprise. Money movers use various methods, including money laundering through legitimate businesses, hawala-like informal funds transfer networks, and traditional financial institutions, to pass IMB revenue to its investors in the United States and abroad.”

Many states and cities acknowledge these gaps and have worked to address them, with varying degrees of success, through efforts to strengthen the regulatory mechanisms overseeing massage practitioners and licensees.28

- Gaps in the U.S. visa and immigration system are exploited to provide recruited workers with the promise of opportunity in the United States. As with many forms of human trafficking involving exploitation of foreign national victims in the United States, “recruiters spot, assess, and recruit new victim-workers abroad, and visa-procurers assist victim workers in creating the false backstories they need to apply for U.S. visas. Enforcers threaten victim workers or their families back home to ensure compliance.” 29

Business Drivers of the Illicit Massage Industry: Exploitation of Worker Vulnerabilities

With regard to exploitation of recruited victim workers, as with other forms of human trafficking, traffickers exploit vulnerabilities unique to foreign national victims and survivors, including language and cultural barriers. In particular, traffickers utilize the following means of coercion and control over workers in IMBs that prevent them from self-identifying or reaching out for help:30

- Fear and shame– a worry instilled by perpetrators that victims have committed criminal acts and will be arrested or deported31

- Debt bondage – an accrued debt that cannot reasonably be paid back and/or existing debt that is exploited

- Lack of knowledge – a gap in understanding of U.S. cultural and legal norms (such as legal rights for workers)

- Controlled movement and isolation – limitation of a victim’s travel outside of the business and the trafficker’s confiscation of a victim’s passports/immigration papers, as well as isolation exacerbated by language barriers

In the 2018 Polaris report, Restore NYC, a service provider serving foreign national survivors of trafficking, including individuals trafficked through IMBs, shared an example of how IMB operators exploit traditional social constructs and cultural norms for nefarious purposes of control and coercion:

“The boss pretended to be a ‘big sister’ to the [victim], communicating to her that we all have to do what is ‘necessary’ for family and their benefit. This hit the heart of the client, and she felt immediately connected to the boss because the boss ‘understood’ her situation and why she was in this country. The client no longer felt ’alone.’ The boss further won her trust by providing free transportation from where she lived to the workplace. This is just a recent example of the trust-building process, that ultimately the boss used to deceive and coerce the client into providing sex services. This parlor was raided by law enforcement, and the client was referred to Restore, where shortly after, we identified her as a survivor.”32

How does the field move forward?

To effectively disrupt a form of trafficking driven by transnational organized criminal networks, new approaches are urgently needed to effectively and sustainably disrupt and dismantle the illicit massage industry. In October 2019, nearly 300 counter-trafficking leaders from across the United States representing state, federal, and local law enforcement agencies, service providers, advocacy non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and government officials gathered to assess the state of the field and identify new solutions.

Part two of this series will explore how communities across the United States are moving beyond arresting survivors and one-off storefront closures. Instead, they are finding new ways to effectively and sustainably combat the pervasive labor exploitation and sex trafficking driven by the Illicit Massage Industry.

*With appreciation for the Heyrick Research team’s insight and expertise.

- 1 Polaris, “Human Trafficking in Illicit Massage Businesses,” 2018, p. 10. https://polarisproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Human-Trafficking-in-Illicit-Massage-Businesses.pdf. Accessed 19 Jan 2020. According to Praesidium Partners’ analysis of Rubmaps data, as of December 2019 there were 10,058 suspected illicit massage businesses marked as “open” and “erotic” in all 50 states. California had the largest number of suspected IMBs (2,482), while South Dakota had the smallest number of suspected IMBs (2). Please note that Praesidium Partners is becoming Heyrick Research in 2020, and is referenced as such in the rest of the footnotes for this article.

- 2 And that’s the lower bound estimate. In 2018, Polaris issued a report estimating the prevalence of IMBs to be more than 9,000. A recent review of Rubmaps data by Heyrick Research staff estimates that number to be closer to 10,058 as of December 2019.

- 3 Heyrick Research documents new and ongoing state, federal, and local cases in its monthly Illicit Massage Industry news update. In December 2019 alone: Two IMBs were shut down in Redlands, California; two individuals were arrested for “human trafficking for the purpose of pimping, pimping, money laundering, and tax evasion” through IMBs in the Bay Area; a woman in Mt. Pleasant, Pennsylvania, pled guilty to human trafficking through the four Tokyo Massage Parlors she operated in Murrysville, Delmont, and Monroeville; two owners in Duluth, Minnesota pled guilty to felony counts of racketeering and failing to pay taxes for their roles in operating IMBs where victims told police “they worked as long as 12 hours a day, six or seven days a week,” were fed rice, and had to pay a daily rate of $10, which was deducted from their wages, to stay at the operators’ homes.

- 4 Polaris, “Human Trafficking in Illicit Massage Businesses,” 2018, pp. 19-26. https://polarisproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Human-Trafficking-in-Illicit-Massage-Businesses.pdf. Accessed 19 Jan 2020. In its report, Polaris “analyzed more than 17,500 Mandarin-language website ads fraudulently recruiting women into jobs within massage establishments in three port cities: Flushing, N.Y.; San Francisco; and Los Angeles…About 8 percent of the recruitment ads explicitly promised that no sex is required for the job, but almost double that number had ads that could be directly linked to commercial sex websites like Rubmaps.com or Spahunters.com. It is important to note that the connection to commercial sex ads or websites demonstrates that the job ads are inherently fraudulent, meeting the standard of ‘force, fraud, or coercion’ necessary to prove human trafficking.” (p. 23)

- 5 Id.

- 6 Id., p 12. As Polaris states, “It is not known exactly how many women working in massage parlors today are trafficked…cultural shame combined with elements of force, fraud, and coercion — the very elements that make up the crime of trafficking — often lead women arrested at illicit massage businesses to insist to police that they are performing commercial sex acts of their own free will. Even when law enforcement is familiar with this type of trafficking and prepared for this answer from potential victims, it can be very difficult for victims to speak about sex or sexual exploitation at all.” Additionally, Polaris notes that “There may be women who choose to sell sex either along with or under the guise of massage therapy, but evidence suggests that many of the thousands of women engaging in commercial sex in IMBs or “massage parlors” are victims of human trafficking” (p. 5).

- 7 Sean M. Crotty & Vanessa Bouché (2018): The Red-Light Network: Exploring the Locational Strategies of Illicit Massage Businesses in Houston, Texas, Papers in Applied Geography, DOI: 10.1080/23754931.2018.1425633, p. 3.

- 8 Nicholas Kulish, Frances Robles and Patricia Mazzei. “Behind Illicit Massage Parlors Lie a Vast Crime Network and Modern Indentured Servitude,” The New York Times. 2 March 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/02/us/massage-parlors-human-trafficking.html. Accessed 19 Jan 2020.

- 9 Id, p. 19. “Women in already precarious financial situations are often lured into hiring expensive brokers to handle the visa process (often fraudulently) and arrange plane tickets and associated fees. To pay the broker, women take out loans ranging from $5,000 to $40,000 depending on the route and travel methods, and the broker used.” Other forms of trafficking involving foreign national victims also entail significant debt bondage. In a 2014 report conducted by Urban Institute and Northeastern University, researchers found that “upon meeting with their recruiters, particularly those affiliated with an employment agency, survivors were often asked to sign a contract but given little or no time read the document, which was sometimes written in a language other than their own…These contracts, and the recruitment process in general, typically involved high fees charged to victims” (pp. 50-51). Additional cases documenting debt bondage include:US v. Intarathong, et al, No. 16-CR-257-DFW/TNL-1 (D. Minn. 2016) [Warren Complaint, Dkt#1 at p. 10] (asserting that recruited victims entered into a contract, or debt bondage, with the trafficker ranging from $40,000 – $60,000 in exchange for a visa and travel to the United States).Kokar v. Gonzalez, No. 05-4641 (7th Cir 2007) (discussion of Kokar’s $45,000 dollars of debt).

- 10 Polaris, “Human Trafficking in Illicit Massage Businesses,” 2018, p. 25. https://polarisproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Human-Trafficking-in-Illicit-Massage-Businesses.pdf. Accessed 19 Jan 2020.

- 11 For example, in an October 2019 police raid of Jade Spa in Dallas found “seven young women were found sleeping on tattered slivers of insulation.” Wilonsky, Robert, “How vice cops linked Southlake’s popular Dragon House to a Dallas massage parlor and beyond,” The Dallas Morning News, 7 Nov 2019. https://www.dallasnews.com/news/commentary/2019/11/07/following-the-money-trail-cops-used-to-link-dallas-jade-spa-to-southlakes-dragon-house-and-beyond/. Accessed 19 Jan 2020.

- 12 Polaris, “Fake Massage Businesses in the United States,” 2011. Accessed December 31, 2019. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/sites/default/files/Fake%20Massage%20Businesses%20AAG.pdf. Recent demand studies show some level of variance in clients served per day across cities. Two studies of Texas cities indicate higher numbers of customers per day than the 6-10 average. A 2017 study by Sean Crotty and Vanessa Bouche of Texas Christian University estimated that Houston’s 292 IMBs served an average of 12 customers per day (p. 14). A study by the NGO SEE estimated that the 21 Dallas-based IMBs sampled in their study served an average of 22 customers per day (SEE, “Estimating the Demand and Gross Annual Economy of Illicit Massage Businesses in Dallas, Texas,” January 2019).

- 13 United States v. Noppawan Lerslurchachai, No.16-CR-257 DWF/TNL (D. Minn. 2016). Lerslurchachai Complaint at p. 12 ¶15 (“For example, CI-1 explained that if a flower received $170 for a commercial sex transaction, $70 would be paid to the house boss and $100 would be sent to the boss/trafficker to pay down the flower’s bondage debt. The flowers are allowed to keep any tips they earn (which can be generated by treating a customer ‘well,’ including engaging in sex without a condom), but may be charged additional fees by either the house boss or the boss/trafficker for expenses such as condoms, lubricant, food, and transportation.”)

- 14 Cases across the country provide evidence of the use of force, fraud, and coercion to deter women from leaving the employ of IMBs. In a landmark 2018 case in Minnesota, five defendants were convicted “by a federal jury for their roles in operating a massive international sex trafficking organization that was responsible for coercing hundreds of Thai women to engage in commercial sex acts across the United States… Thirty-one defendants previously pleaded guilty for their roles in the sex trafficking organization.” According to the U.S. Department of Justice’s December 13, 2018, press release through the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Minnesota: “The organization also engaged in widespread visa fraud to facilitate the international transportation of the victims. Traffickers assisted the victims in obtaining fraudulent visas and travel documents by funding false bank accounts, creating fictitious backgrounds and occupations, and instructing the victims to enter into fraudulent marriages to increase the likelihood that their visa applications would be approved. Traffickers also coached the victims as to what to say during their visa interviews. While working to obtain visa documents, traffickers gathered personal information from the victims, including the location of the victims’ families in Thailand. This information was later used to threaten victims who sought to flee the organization in the United States.” https://www.justice.gov/usao-mn/pr/thirty-six-defendants-guilty-their-roles-international-thai-sex-trafficking-organization

- 15 Vanessa Bouche & Sean M Crotty (2017): Estimating demand for illicit massage businesses in Houston, Texas, Journal of Human Trafficking, DOI:10.1080/23322705.2017.1374080. Accessed 18 Jan 2020. Footnote 12 on page 15 of the study states: “…(T)his is a roughly $2.8 billion industry in the United States. Though this estimate is flawed in that we use numbers from one city to extrapolate to the country, it is perhaps the most empirically-grounded estimate to date of the profitability of the illicit massage industry.” Polaris estimated the IMI to earn some $2.5 billion in revenue in the United States (Polaris, “Human Trafficking in Illicit Massage Businesses,” 2018, p. 8). Given Heyrick Research’s December 2019 analysis of Rubmaps data, if there are approximately 1,000 more suspected IMBs marked as “open” and “erotic” than the 9,000 suspected IMBs at the time of the 2018 Polaris study, total revenue in the United States is likely higher than $2.8 billion.

- 16 Polaris, “Human Trafficking in Illicit Massage Businesses,” 2018, p. 5. https://polarisproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Human-Trafficking-in-Illicit-Massage-Businesses.pdf. Accessed 19 Jan 2020. A quick online search of local news stories covering police investigations of IMBs regularly highlights IMBs operating openly in strip malls and well-trafficked centers of commerce in communities across the United States. See for example a July 2019 story from Northeast Ohio (https://www.wkyc.com/article/news/crime/authorities-raid-more-than-a-dozen-northeast-ohio-massage-parlors-in-human-trafficking-probe/95-6c4be769-3017-45e8-909e-0b01d712447c); an October 2019 story from Belton, Missouri (https://fox4kc.com/2019/10/31/two-belton-massage-parlors-raided-ending-with-employee-arrested-for-prostitution/); and, an April 2019 story from Sacramento, CA (https://www.abc10.com/article/news/local/sacramento/this-problem-is-everywhere-sacramento-cracking-down-on-illicit-massage-parlors/103-0667a6a8-7a99-440f-94aa-76296dd8fa56). Accessed 19 January 2020.

- 17 Through its initiative to map IMBs throughout the state of Texas, Houston-based NGO Children at Risk found that “IMBs are not relegated only to the seedy parts of town…we found IMBs were often located in or near affluent areas.” Children at Risk, “Local Government Guide: Illicit Massage Business Eradication Toolkit,” March 2019, p. 5. https://childrenatrisk.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Municipal-Ordinances-IMB-Toolkit-2-1.pdf.

- 18 Sean M. Crotty & Vanessa Bouché (2018): The Red-Light Network: Exploring the Locational Strategies of Illicit Massage Businesses in Houston, Texas, Papers in Applied Geography, DOI: 10.1080/23754931.2018.1425633, p. 21.

- 19 Evidenced by various indicators, including a steady increase in signals nationally (a mark of public awareness) to the National Human Trafficking Hotline between 2012 and 2018 (see https://humantraffickinghotline.org/states) and trends in federal case data, which indicate an overall increase in initiated federal sex trafficking cases, (but stagnant growth in initiated labor trafficking cases). See the Human Trafficking Institute’s 2018 review of federal case data for more details.

- 20 Adapted from Polaris, “Human Trafficking in Illicit Massage Businesses,” January 2018.

- 21 Rachel Axon, Cara Kelly and Michael Braun. “Sex trafficking is behind the lucrative illicit massage business. Why police can’t stop it,” USAToday, 30 July 2019. https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/investigations/2019/07/29/sex-trafficking-illicit-massage-parlors-cases-fail/1206517001/. Accessed 8 December 2020.

- 22 According to Bob Houston of Praesidum Partners, “Numerous case examples bear out evidence of visas fraudulently facilitated by transnational organized crime elements overseas” (Personal interview, 6 Jan 2020). Case examples include:United States v. Kang, et al, No. 06-CR-298-JCC-JPD (W. D. Wash. 2006) [Criminal Complaint, Dkt#1 at p. 133] (providing multiple accounts of trafficked workers who overstayed their temporary visas, and victims arriving in the U.S. whose visas had already expired prior to their arrival in the United States).United States v. Unruean Aboulafia, No. 13-CR-65-JCC (W. D. Wash. 2013) [Plea Agreement, Dkt# 154 at pp. 5-6] (describing actions of trafficker and her network to facilitate travel of victims on overstayed visas from Asia and throughout the United States to engage in illicit sex work).United States v. Intarathong, et al, No. 16-CR-257-DFW/TNL-2 (D. Minn. 2016) [Boonluea Complaint, Dkt# 1 at p. 18] (citing trafficker coaching victims to give false statements to U.S. Embassy officials during the visa application and interview process).

- 23 According to Demand Abolition, “Only about 6% of men who purchase sex illegally report ever having been arrested for it.” From “Who Buys Sex: Understanding and Disrupting the Illicit Demand Market,” November 2018. https://www.demandabolition.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Demand-Buyer-Report-July-2019.pdf

- 24 Recent examples include the 2018 Minnesota case: “…(L)aw enforcement traced tens of millions of dollars to the organization…at trial, there was testimony that more than $40 million was sent to Thailand by one money launderer alone.” https://www.justice.gov/usao-mn/pr/thirty-six-defendants-guilty-their-roles-international-thai-sex-trafficking-organization. A 2019 law enforcement investigation of IMBs on Emerald Street in Northwest Dallas found that of $6.5 million in revenue deposited in banks and casinos, $5 million was funneled through casinos in Oklahoma by the IMB owners. https://www.wfaa.com/article/news/sex-trafficking-ring-suspects-may-have-made-millions-and-tried-to-hide-it-at-casinos/287-2c78c282-ed6d-441c-8c99-057159aa019b

- 25 From Heyrick Research’s own internal analysis of existing studies and sources.

- 26 Sean M. Crotty & Vanessa Bouché (2018): The Red-Light Network: Exploring the Locational Strategies of Illicit Massage Businesses in Houston, Texas, Papers in Applied Geography, DOI: 10.1080/23754931.2018.1425633

- 27 Nicholas Kulish, Frances Robles and Patricia Mazzei. “Behind Illicit Massage Parlors Lie a Vast Crime Network and Modern Indentured Servitude,” The New York Times. 2 March 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/02/us/massage-parlors-human-trafficking.html

- 28 Ohio and Texas are two examples of states working to increase oversight, training and resources for agencies inspecting and licensing massage businesses.

- 29 Houston, Bob, CEO of Praesidium Partners (soon to be Heyrick Research). Personal Interview. 2 December 2019.

- 30 List adapted from 2018 Polaris study. Additionally, “victims are much more likely to share information about labor exploitation they have experienced” compared to information about their sexual exploitation. Polaris, “Human Trafficking in Illicit Massage Businesses,” 2018, p. 10. https://polarisproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Human-Trafficking-in-Illicit-Massage-Businesses.pdf. Discussion of cultural social constructs and dynamics on p. 32.

- 31 The U.S. Department of Justice’s Office for Victims of Crime Training and Technical Assistance Center provides a list of vulnerabilities facing foreign national victims (https://www.ovcttac.gov/taskforceguide/eguide/4-supporting-victims/45-victim-populations/foreign-national-victims/). Accessed 19 Jan 2020.

- 32 Polaris, “Human Trafficking in Illicit Massage Businesses,” 2018, p. 32. https://polarisproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Human-Trafficking-in-Illicit-Massage-Businesses.pdf. Accessed 19 Jan 2020. Polaris provides more detailed information on how traffickers exploit social constructs and norms on page 32, based on interviews with survivors, culturally competent service providers and organizations, as well as academic research.