“Every year, we must remind successive generations that this event triggered a series of events that one by one defines the challenges and responsibilities of successive generations. That’s why we need [Juneteenth].” – Texas Representative Al Edwards

By: TAYLOR KING

There are several moments in American history that signify victories in ending slavery in the United States. They include Abraham Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at the close of the Civil War, or the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the United States’ Constitution, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude. And yet, despite the significant weight of these events in history, the moment recognized as the major turning point for slavery in the United States is rarely mentioned in history books—Juneteenth.

Juneteenth took place June 19, 1865, in Galveston, Texas—far from the national spotlight.

At the time, despite Lincoln’s best attempts to preserve the Union, the Emancipation Proclamation still wielded little power in any territory not yet controlled by the Union. Slave owners in Confederate states often sought out loopholes for maintaining the status quo, hoping to hold onto their human property as long as possible. As a result, many slave owners moved deeper into southern territory. Due to the minimal number of Union troops enforcing the Emancipation, a particularly compelling opportunity was available in one state —Texas.

Due to Texas’ strategic location along the Gulf, the state produced crops throughout the war and sold them to their neighbors across the border. When other Southern states found their supply lines cut off by the Union armies, Texas held fast as the backdoor” to the Confederacy. Using its crop revenue from key relationships with neighboring countries to fund continued war efforts, Texas played a vital role in the conflict.

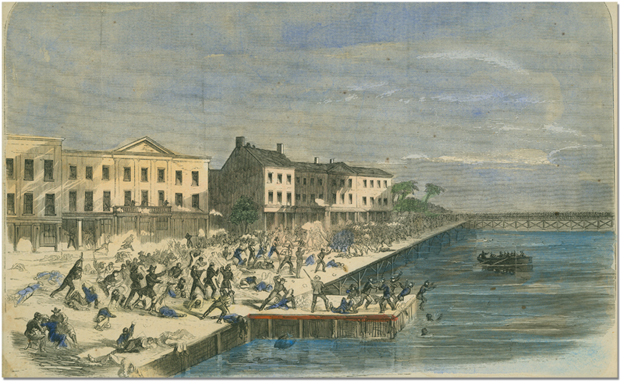

Texas State Library and Archives Commission

In 1865, Galveston was the largest city in Texas and responsible for three-quarters of the state’s seaborn cotton exports.1 And in the mid-1800s, where there was cotton, there were slaves.2 Throughout the war, the city endured Union troops’ advancements – from blockades and besiegement to attempts at capture – holding their position even after the fall of the Confederacy itself.

Once Confederate General Lee surrendered at the Battle of Appomattox Court House in April 1865, news of liberation traveled quickly throughout the newly reunited States. At the time, it was common for messages to take several days, or even a few weeks, to arrive at their destination.3 Texas, however, was late to the game.

Once the war was over, the task of securing the District of Texas and enforcing the Emancipation was given to Union General Gordan Granger. On June 19, 1865, more than two months after Gen. Lee’s surrender, Granger delivered a speech to the slaves in Texas and their masters:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free…”

The words sparked outward shows of elation for “freedmen” who celebrated their newfound freedom, but the hopes in Galveston soon melted into a harsh reality. Efforts to embrace freedom were met with severe opposition by slaveowners who were not ready to relinquish their human capital.

Former slave Susan Merritt recalled,4

“‘You could see lots of [former slaves] hangin’ to trees in Sabine bottom right after freedom, ’cause they cotch ’em swimmin’ ‘cross Sabine River and shoot ’em.’”

One former slave continued working for her mistress for six years saying, “she’ whip me after the way just like she did ‘fore.”5 Sadly, the struggle for human rights was not over — it had only just begun.

Although change didn’t happen overnight, the freed slaves in Galveston used Juneteenth to begin claiming their victory. Gathering together each year, freed slaves used the day to measure progress against freedom and encourage one another in their path forward.

For decades, Juneteenth remained a holiday for former Galveston slaves and their descendants. Over time, word of the celebration traveled across state lines the way the best stories do — by word of mouth. “The people from Texas took Juneteenth Day to Los Angeles, Oakland, Seattle, and other places they went,” wrote Isabel Wilkerson in Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery. But it was the Civil Rights Movement that eventually blasted the event into the national spotlight.

Shortly after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination in the spring of 1968, a Poor People’s March was organized by many of the civil rights leaders including Dr. King’s close friend, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, and his widow, Coretta Scott King. When it became clear the march’s goals would not be reached, the group chose a different way to commemorate their loss and fight for their future — Juneteenth.

Today, 43 states recognize Juneteenth as a national holiday. Celebrations often range from small backyard cookouts to national events and dedications. Juneteenth is more than a day of remembrance. It is a day to measure the nation’s progress in battling inequality, no matter how slowly it comes.

This Juneteenth, much like the first, there is hope for a nation devoid of slavery. And until that nation is ours, we must continue to rally behind that dream.

- 1 Matheson, David. “Galveston in the Civil War.” East Texas History. Accessed June 19, 2019. https://easttexashistory.org/items/show/160.

- 2 “The Cotton Economy and Slavery.” PBS. Accessed June 19, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/video/the-cotton-economy-and-slavery/.

- 3 “1850-1877: Communications: Overview.” American Eras. . Encyclopedia.com. (June 19, 2019). https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/1850-1877-communications-overview

- 4 Litwack, Leon F. Been in the Storm so Long: The Aftermath of Slavery. New York: Knopf, 1981.

- 5 Cantrell, Gregg, and Elizabeth Hayes. Turner. Lone Star Pasts: Memory and History in Texas. College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2007.