By: MEGAN ABRAMEIT

On this day in history, Frederick Douglass escaped slavery — a day he would later describe as the day his “free life began.”

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery as Frederick Washington Bailey on a Maryland plantation in 1818. From there, he moved locations but never escaped the status as a slave. At the age of seven, his master sent him off the plantation to work in Baltimore in the household of Hugh Auld, where he learned to read. At the age of 15, he was “loaned” to a plantation belonging to Thomas Auld, his master’s brother. Because of Douglass’s ability to read, Thomas Auld considered him “dangerous,” and after many infractions, he eventually was sent back to Baltimore because Auld had unfurled his plan for escape.

Now older, Douglass worked for Hugh Auld as a caulker (inserting materials in between shipboards to make the boat waterproof) in a Baltimore shipyard. The shipyard was an unusual place as Douglass worked alongside white workers and freed black men, although himself still a slave. Although Douglass states he was allowed relatively more freedom working in the shipyards and his “condition was, comparatively a free and easy one,” the psychological toll of slavery continued to oppress him. He writes, “The practice, from week to week, of openly robbing me of all my earnings, kept the nature and character of slavery constantly before me.”

Douglass knew he needed money if he was going to escape, so he asked Hugh Auld if he could take on extra work with other employers to save money, as long as he continued paying Auld a large portion of his earnings. While this practice was not unheard of, due to Douglass’ status as an “untrustworthy” slave resulting from his history of running away, his request was denied. He appealed again two months later, and Hugh Auld agreed to it because it would mean he would no longer need to “provide” for Douglass. As a slave who worked for additional employers, Douglass would have to pay for his food, board, clothing, and working materials while additionally handing over a significant portion of his earnings directly to his master.

Through constant work, Douglass managed to save up a little money over the course of three months. However, upon leaving Baltimore without his master’s permission, he lost this small freedom. Hugh Auld’s promise of retaliation to make Douglass’s life more difficult than ever made Douglass decide to leave as soon as possible. He believed this would be his final chance, because if unsuccessful in this second attempt, he knew he would be sent to the Deep South, where a new master would watch him closely making the long, perilous escape journey to the North impossible.

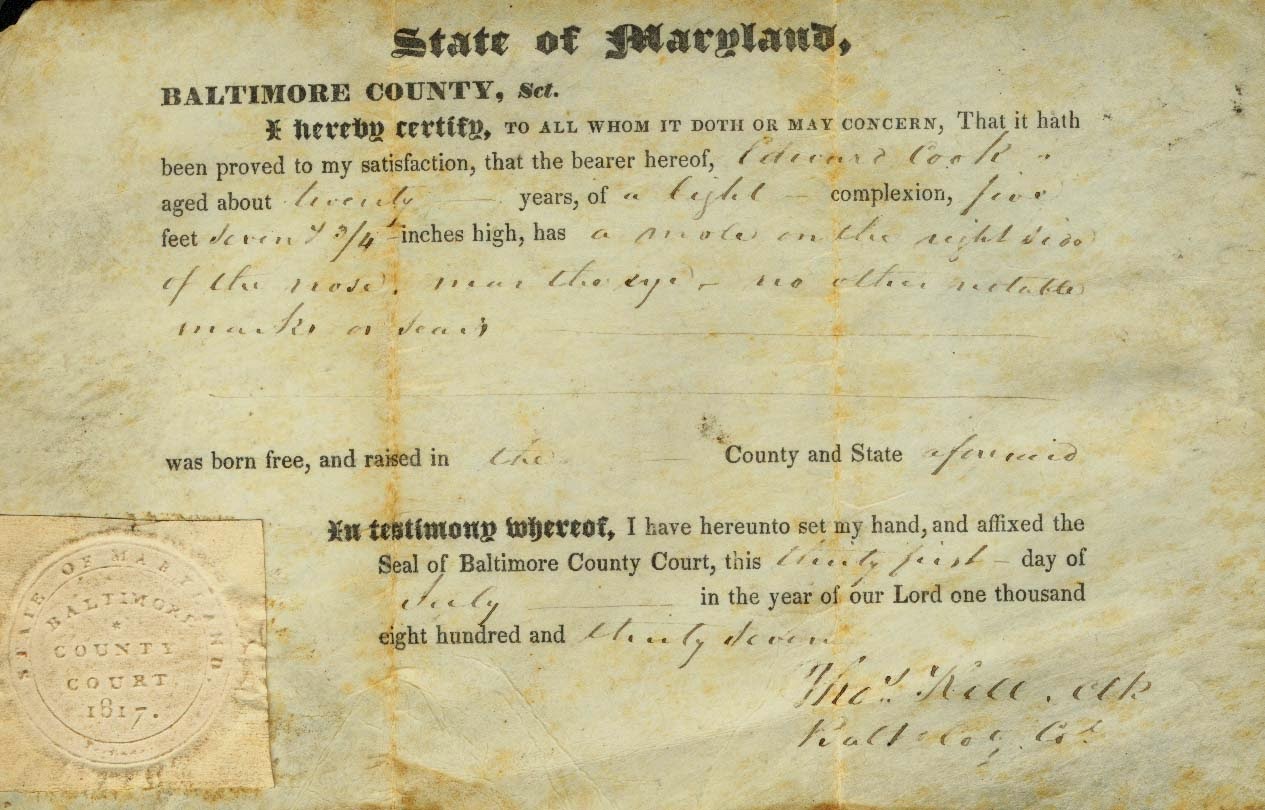

In 1838, Maryland required freed black people have “free papers” that documented their free status. The papers were extensive, describing in detail the person’s physical characteristics, and it was common that a slave would escape to the North by borrowing a freed person’s papers. This was dangerous because if someone caught the slave both him and the freed person would lose their freedom, but empathy and generosity compelled the freed. Unfortunately, Douglass didn’t fit any of the descriptions of his friends with free papers. However, this didn’t stop him from borrowing papers. While Douglass was much lighter skinned than the description of his friend, he borrowed his “sailor’s protection” papers, which although not free papers were sometimes accepted as much.

On September 3, 1838, at 20 years old, Douglass donned the traditional sailor’s outfit of a red shirt, tarpaulin hat, and a black scarf tied around his neck. Unable to risk buying a ticket at the office where he would be under scrutiny, Douglass hopped on a moving train bound for Havre de Grace, Maryland, and found a seat among other freed people of color.

Sailors were more respected than others in the port city of Baltimore, and Douglass was sure he could play the part. From his time working on shipyards, Douglass “could talk sailor like an ‘old salt.’” As the conductor made his way through the train checking papers, Douglass knew his “whole future depended upon the decision of this conductor.” When Douglass did not quickly show his papers, the conductor asked,

‘I suppose you have your free papers?’ To which I answered:

‘No, sir; I never carry my free papers to sea with me.’

‘But you have something to show that you are a freeman, haven’t you?’

‘Yes sir,’ I answered: ‘I have a paper with the American eagle on it, and that will carry me around the world.’

The conductor glanced at the paper and continued. This was the first of many hurdles Douglass would cross on his path to freedom. Many people worked as slave catchers along popular escape routes, and Douglass made several transfers between ships and trains as he tried to reach New York. At one point in the journey, Douglass encountered a blacksmith who had worked with him at the shipyards. Although he was sure the man recognized him, the man did nothing. When he finally reached Philadelphia, he boarded the final train to New York, where he arrived the next morning. In 24 hours, Douglass had won his freedom.

When asked about the moment he landed in New York, Douglass wrote1, “I felt as one might supposed to feel, on escaping from a den of hungry lions. But, in a moment like that, sensations are too intense and too rapid for words. Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be described, but joy and gladness, like the rainbow of promise, defy alike the pen and pencil.”

After his arrival, he wrote for his future wife, a freed black woman named Anna Murray, to meet him in New York. They had become engaged while in Baltimore. After their hasty marriage in 1838, they traveled to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where they hoped Douglass could find work as a caulker.

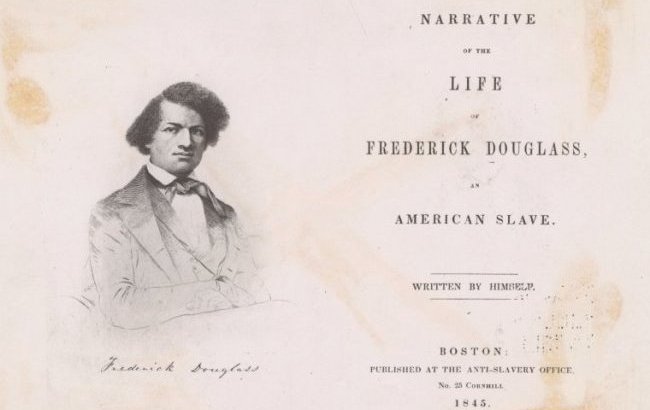

After arriving in New Bedford, he joined the Northern abolitionist movement. He began to speak at abolitionist meetings about his experiences as a slave, which in turn blossomed into speaking all over the North, and in 1845, he published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. However, with this new found fame, there was concern of him being captured and re-enslaved, so Douglass traveled overseas.

Frontispiece and title page of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave.Boston: Published at the Anti-Slavery Office, 1845.

For nearly two years, he gave speeches and sold copies of his autobiography in England, Ireland, and Scotland. When a group of abolitionists offered to purchase his freedom, Douglass accepted. Once back in the United States as a truly free man, he continued to share his story and educated presidents, government officials, and the public alike about the evil of slavery and the need for emancipation.

Douglass’ legacy as a pioneering abolitionist continues to inspire, and it started with his courage to jump on a train 180 years ago today.

- 1 Douglass, Frederick. “Chapter 22: Liberty Attained.” My Bondage and My Freedom. Lit2Go Edition. 1855. Web. <http://etc.usf.edu/lit2go/45/my-bondage-and-my-freedom/1500/chapter-22-liberty-attained/>