“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

– The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

By: TAYLOR KING

Today, 22 different regional and national constitutions recognize the freedom to assemble as a basic human right,1 and more than 20 countries acknowledge their citizens’ right to freedom of speech.2 For Americans, the Founding Fathers assured access to these rights 230 years ago today — September 25, 1789 — in the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

These rights were not afforded to the American colonists while under British rule. Therefore, many of the tenants established in the First Amendment were a direct response to the injustices colonists experienced prior to the American Revolution. However, when it came time for the colonists to govern themselves, they found the process of defining their rights painstakingly difficult.

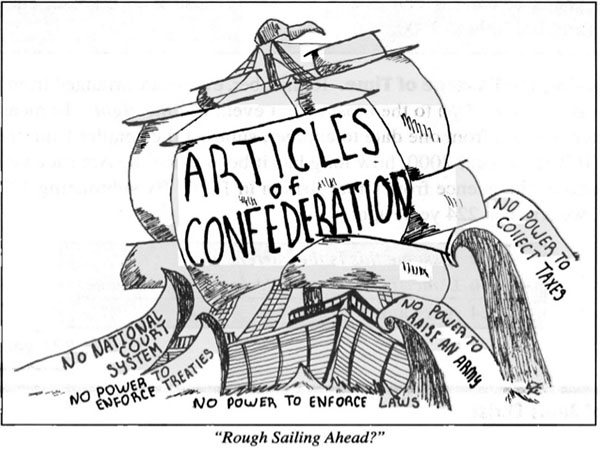

The first document used to govern the people after the Revolutionary War was the Articles of Confederation. However, the document lacked basic governmental functions — imposing taxes, building a military, and conducting foreign policy, to name a few.3 So, the original 13 states appointed 70 delegates (55 attended) to convene in Philadelphia for the Constitutional Convention, intending to fill in these gaps by offering amendments to the Articles. After much debate, however, the group determined the need for an entirely new document.

The convention pinged James Madison as the chief architect of this new governing document. In fact, his Virginia Plan served as the blueprint4 for what became the Constitution of the United States. Over the next four months, the men debated everything from proper state representation to the issue of slavery, each delegate advocating for his own state’s agenda. Finally, on September 15, 1787, the convention adopted their final draft of the Constitution, leaving it up to the states to ratify the document into law.

Opponents of the Constitution’s ratification latched onto one major flaw: the lack of a Bill of Rights.5 This addition was essential, the First Congress insisted, “to prevent misconstruction or abuse of [the Constitution’s] powers” and to extend “the ground of public confidence in the government.”6 The Federalists (proponents of immediate ratification), however, thought a Bill of Rights was not only unnecessary but dangerous. They wrote letters to the public — the Federalist Papers — pleading for a simplistic Constitution, afraid a Bill of Rights would limit the people rather than protect them.7 In the end, the Federalists won — narrowly — with a vote of 55 to 398

Next, the states needed to sign on. The first five states passed with little disagreement. Then, on February 6, 1788, in a move known as the Massachusetts Compromise, Massachusetts voted to ratify the Constitution with a 53% majority only after including a provision for immediate amendments.9 Maryland and South Carolina followed shortly after. Then, on June 21, 1788, New Hampshire became the 9th state to ratify using Massachusetts’ strategy — ensuring amendments would be swiftly added to provide citizens with basic rights. This vote made it official. The Constitution was the official framework of the U.S. Government.

“Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States.” 1940. Oil-on-canvas painting by Howard Chandler Christy.

Knowing this moment was critical to building the states’ trust, Madison immediately began working on a proposal for constitutional amendments. During the drafting stages, Madison received a great amount of pressure from Thomas Jefferson, who persuaded Madison to make certain rights a top priority.10

After reviewing a large list of desires from various state legislators, Madison submitted his first draft to Congress. Congress then whittled down the original 19 amendments to a final 12, and on September 25, 1789, the Bill of Rights received its stamp of approval. Appearing at the top of the document was Thomas Jefferson’s list of crucial additions — the First Amendment.

The First Amendment begins, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.” This portion is known as the “establishment clause,” because it establishes the separation between church and state. Immediately after this promise, Americans are assured the right to freedom of religion. This statement was a major departure from the norms of government in the 18th Century when religious persecution was virtually universal.11

The Amendment then guarantees freedom of speech. The Founding Fathers intentionally crafted both the Constitution and the Bill of Rights with room for leniency in interpretation. The prohibition of “abridging the freedom of speech” falls right in line. With each new generation, this right adapted, forming the culture of the United States in the process.

The right to freedom of press accompanied the free speech provision, ensuring citizens could not only engage in controversial verbal dialogue but also publish their opinions, no matter their popularity with those in power. If those thoughts and opinions resonated with others, the amendment also protected the right to assemble together and voice these complaints collectively.

Lastly, the First Amendment guaranteed a right to “redressing…grievances” against the government. Since the practice of addressing unconstitutional legislation through lawsuit was not yet established in the United States, this provision allowed for the submission of a petition against the decisions of the federal government. Altogether, these promises stitched together the foundation for the following 11 amendments by assuring American citizens would have the right to protest injustice without fear of being silenced.

After 230 years, the First Amendment holds the same role in the United States — to provide a framework and definition of freedom. It has been tested in more than 870 court rulings (from the U.S. Supreme Court to lower courts).12 It provided a pathway for the Civil Rights movement, appearing in both Edwards v. South Carolina and NAACP v. Alabama court decisions. It protected the right to hold historic assemblies like the March on Washington in 1963 and the Million Man March in 1995. And, its established belief systems underpinned the United States’ support of the United Nation’s Declaration of Human Rights.

On this day in history, we recognize the importance of raising a collective voice against injustice, and we remember the work left to be done to ensure all human beings are treated as such.

- 1 “Freedom of Assembly.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, September 20, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freedom_of_assembly.

- 2 Gray, Alex. “Freedom of Speech: Which Country Has the Most?” World Economic Forum. Accessed September 24, 2019. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/11/freedom-of-speech-country-comparison/.

- 3 All That’s Interesting. “Who Wrote The Constitution? A Look Back At The Constitutional Convention.” All That’s Interesting. All That’s Interesting, April 26, 2018. https://allthatsinteresting.com/who-wrote-the-constitution.

- 4 James Madison’s Contribution to the Constitution. Accessed September 24, 2019. http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/madison/aa_madison_father_1.html.

- 5 History.com Editors. “Bill of Rights.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, October 27, 2009. https://www.history.com/topics/united-states-constitution/bill-of-rights.

- 6 National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed September 24, 2019. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/24824259.

- 7 “The Great Debate.” Constitution Facts – Official U.S. Constitution Website. Accessed September 24, 2019. https://www.constitutionfacts.com/us-articles-of-confederation/the-great-debate/.

- 8 Linder, Douglas O. The Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia. Accessed September 24, 2019. http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/conlaw/convention1787.html.

- 9 “Bill of Rights – Timeline.” Issues & Controversies in American History. Infobase Publishing, 25 Apr. 2006. Web. 25 Oct. 2013. http://clic.cengage.com/uploads/ff2082c33fb417a93b5ee61a795831b0_1_3945.pdf

- 10 Head, Tom. “What Are Your 1st Amendment Rights?” ThoughtCo. Accessed September 24, 2019. https://www.thoughtco.com/the-first-amendment-p2-721185.

- 11 Id.

- 12 “The First Amendment Encyclopedia.” Case Categories | The First Amendment Encyclopedia. Accessed September 24, 2019. https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/encyclopedia/case.