“I was born by the river in a little tent

Oh and just like the river I’ve been running ev’r since

It’s been a long time, a long time coming

But I know a change gonna come, oh yes it will”– Sam Cooke, March on Washington, August 28, 1963

By: TAYLOR KING

In 1962, James Meredith made national news when he became the first black man to attend the University of Mississippi. The nation’s response was anything but encouraging.

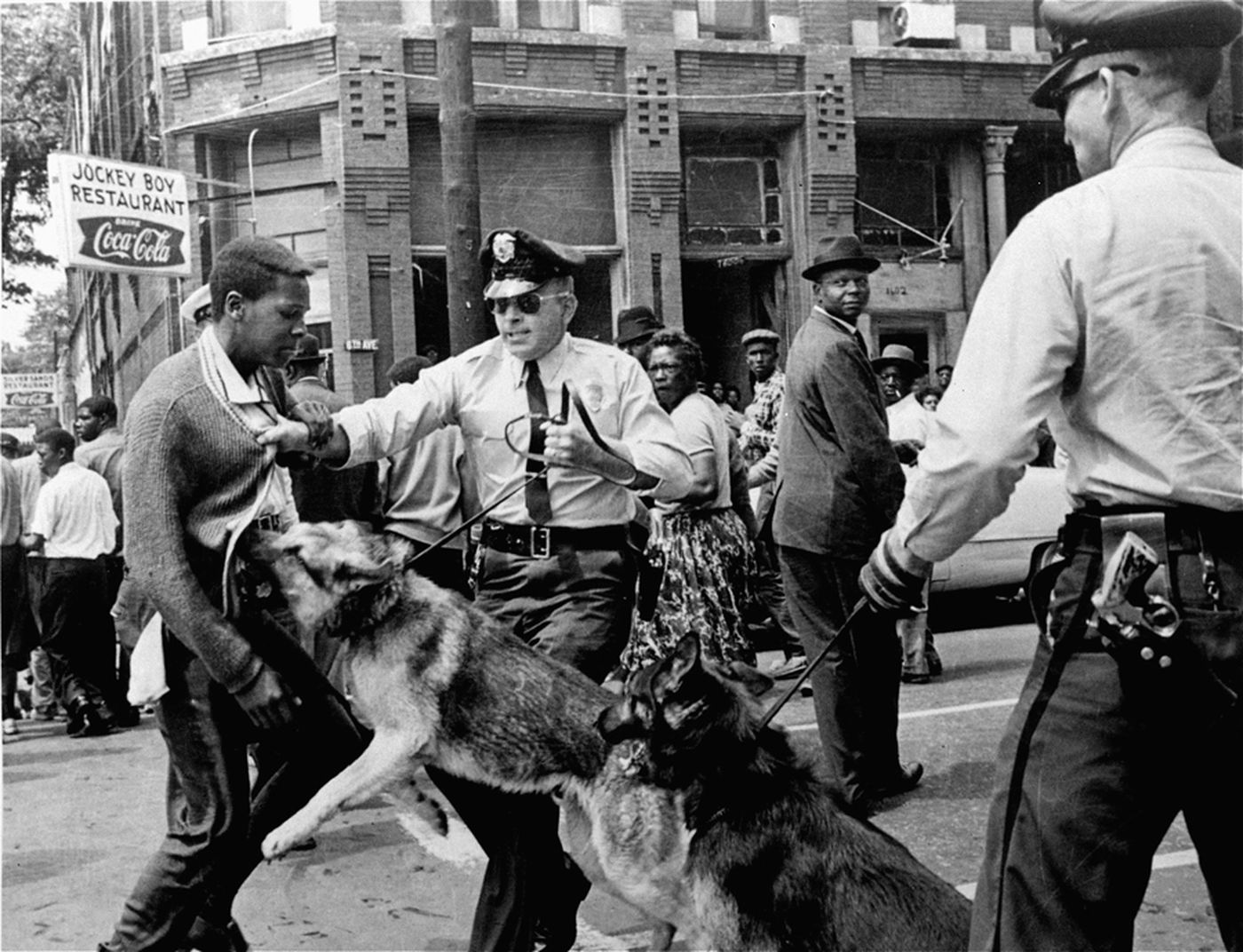

After the desegregation of Ole Miss, violence continued to erupt across the United States as the Civil Rights Movement gained traction. Later that spring, Eugene “Bull” Connor, ordered his police to use fire hoses, police dogs, and nightsticks to deter anti-segregation protestors. And in the summer, Byron De La Beckwith shot and killed Medgar Evers, a civil rights activist, in his own driveway.

Change was coming, but it wasn’t here yet.

A 17-year-old Civil Rights demonstrator is attacked by a police dog in Birmingham, Ala., on May 3, 1963. Image led the front page of the next day’s New York Times. Bill Hudson/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Although 1963 was a year noted for its unrest and civil rights demonstrations, the planning for a March on Washington began more than a decade earlier. In the summer of 1941, the American job market was growing thanks to an increased demand for military supplies during World War II. However, despite the patriotism demonstrated by black Americans on the battlefield, the doors of opportunity were closed for black Americans on the home front.

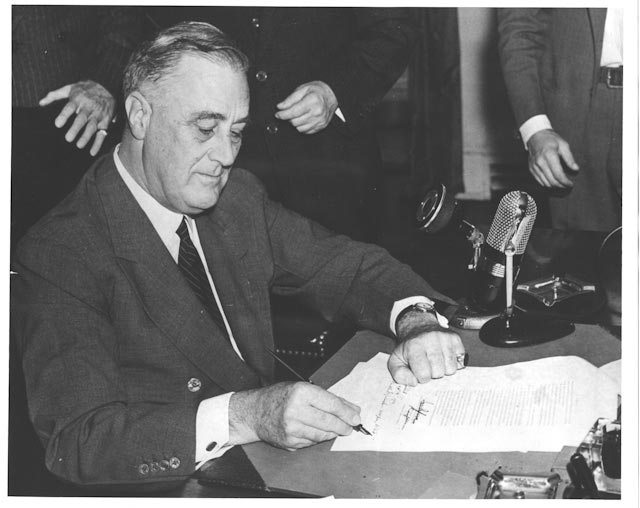

As a result, A. Phillip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), proposed a March on Washington to draw attention to the exclusion of African Americans and persuade President Franklin D. Roosevelt to pass civil rights legislation. It worked. The threat of more than 100,000 marchers in Washington, D.C., convinced President Roosevelt to sign Executive Order 8802, mandating the formation of the Fair Employment Practices Commission to investigate racial discrimination in defense firms.

FDR Library Photograph Collection. NPx # 61-406

Fast-forward to the spring of 1963, and the hopes once triggered by the passage of the Executive Order had been replaced with a bleak reality for black Americans. From high levels of unemployment and minimal wage offerings to dismal job mobility and Southern segregation, the American dream was still far out of reach.

In March of that year, Randolph telegraphed Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. to request his involvement in a march for “Negro job rights.” In May, Secretary Stewart Udall of the U.S. Department of the Interior received a letter from Randolph, with signatures from King, James Farmer of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and Charles McDew of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), requesting a permit for a march culminating at the U.S. Capitol that fall. After notifying President John F. Kennedy of their intent, the date was set for August 28, 1963.

The March had 10 stated goals:

- A comprehensive and effective civil rights bill that would do away with segregated public accommodations

- Withholding of Federal funds from all programs in which discrimination exists

- Desegregation of all public schools in 1963

- Enforcement of the 14th Amendment- reducing Congressional representation of states where citizens are disenfranchised

- A new Executive Order banning discrimination in all housing supported by federal funds

- Authority for the Attorney General to institute injunctive suits when any constitutional right is violated

- A massive federal program to train and place all unemployed workers- Negro and White- on meaningful and dignified jobs at decent wages

- A national minimum wage act that gives all Americans a decent standard of living

- A broadened Fair Labor Standards Act to include all areas of employment presently excluded

- A federal Fair Employment Practices Act barring discrimination by federal, state, and municipal governments as well as employers, contractors, employment agencies, and trade unions

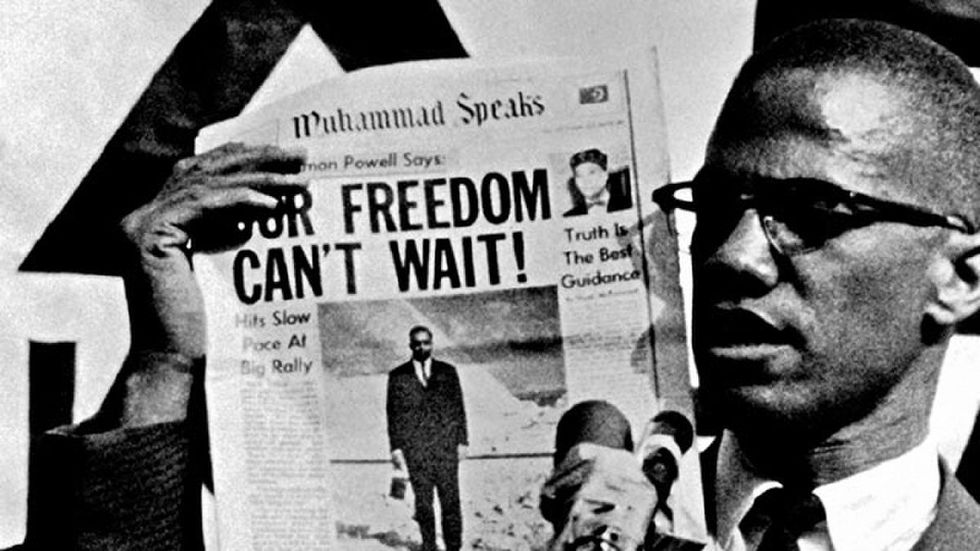

These goals were universally embraced by organizations in the Civil Rights Movement, but the march itself was not endorsed by some key players, namely Malcolm X, who nicknamed the event the “Farce on Washington.”1

Dr. Joyce Ladner, a staunch supporter of the SNCC and march attendee, remembered, “[Malcolm X’s] ideal would have been, you take your freedom, grab it, not ask the government to free you. I do recall very clearly wondering who was right, King and us or Malcolm?”2

Malcolm X is shown in a scene from the documentary “I Am Not Your Negro”

Even President Kennedy, a supporter of civil rights legislation, was apprehensive. On June 22, he met with civil rights leaders to voice his concerns, saying perhaps the march was “ill-timed.” “We want success in the Congress, not just a big show at the Capitol,” he remarked.3

In spite of the pushback, planning for the march continued. Over the next two months, Randolph’s partner, Bayard Rustin, took charge of the day-to-day event planning, including moving the event to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. An early joiner of the movement and a brilliant strategist of nonviolent protests, Rustin coordinated a staff of more than 200 civil rights activists and organizers from arranging travel logistics for the marchers to completing “marshal” training for crowd control. When the planning was complete, Rustin had arranged more than 2,200 chartered buses, 40 special trains, 22 first-aid stations, eight 2,500-gallon water-storage tank trucks, and 21 portable water fountains.

After months of preparation, the day arrived, and along with it came great expectations.

At 5:30 in the morning on August 28, 1963, the air was muggy, and the sky was grey. The Washington mall was empty except for a few reporters who began to tease Bayard saying, “Where are the people?”4

John Lewis, one of the Bix Six leaders, recalls the events that followed. “That morning the 10 of us [the Big Six, plus four other march leaders] boarded cars that brought us to Capitol Hill. Looking toward Union Station, we saw a sea of humanity; hundreds, thousands of people. We thought we might get 75,000 people showing up on August 28. When we saw this unbelievable crowd coming out of Union Station, we knew it was going to be more than 75,000. People were already marching … so what the 10 of us did was grab each other’s arms, made a line across the sea of marchers. People literally pushed us, carried us all the way, until we reached the Washington Monument, and then we walked on to the Lincoln Memorial.”5

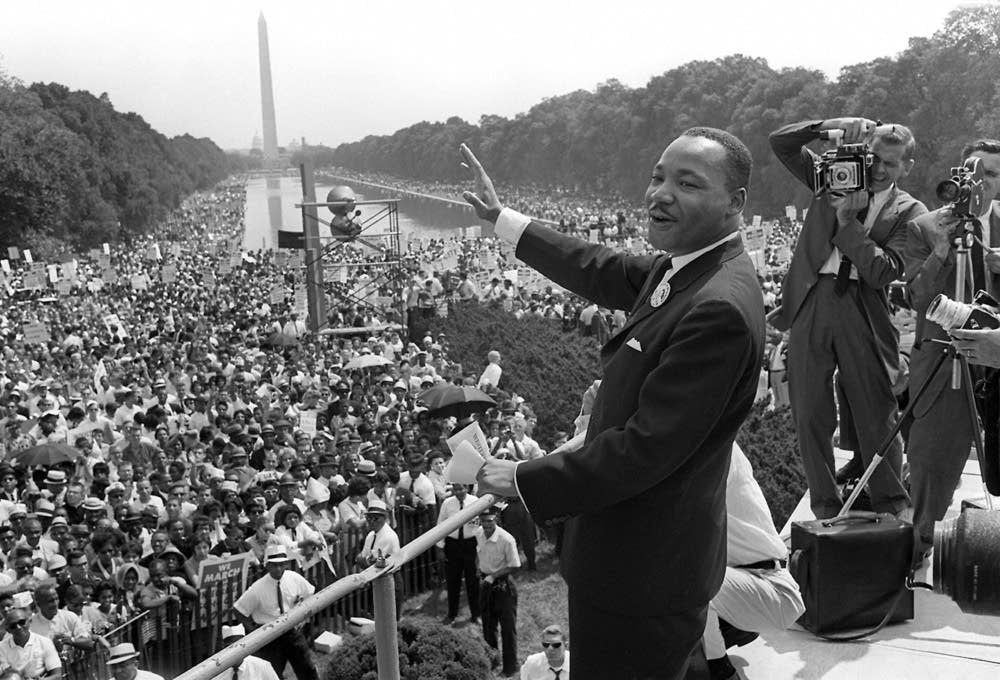

Between 200,000 and 500,000 demonstrators march down Constitution Avenue during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Washington, D.C., August 28, 1963. Hulton Archive | Getty Images 1963

Once all the day’s speakers had taken the stage, the event, more than 10 years in the making, began beneath the words of the Emancipation Proclamation, written exactly 100 years before.

“… I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free…”

Many memorable speeches were given in front of the crowd of more than 200,000 people, but none as repeated as King’s, and the juxtaposition of Lincoln’s words and his own, were not lost on the attendees or those who hear the speech today.

“Even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream,” King said. “… And when that [dream comes true], we will be able to speed up that day when all God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, we will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!’”6

AFP | Getty Images 1963

Ken Howard, a march attendee, remembered coming home to see his mother watching King’s speech on the television, “You could feel the gravity there. It’s difficult for someone these days to understand what it was like, to suddenly have a ray of light in the dark. That’s really what it was like.”7

Now, 55 years later, commentators have noted several consequences of the historic march – most notably, the 1964 Civil Rights Act which outlawed segregation in schools and criminalized employment discrimination based on race, and the Voting Act of 1965 which gave the vote to all people of color.

President John F. Kennedy in the White House with leaders of the civil rights ‘March on Washington’ (left to right) Whitney Young, Dr. Martin Luther King (1929 – 1968), Rabbi Joachim Prinz, A. Philip Randolph, President Kennedy, Walter Reuther (1907 – 1970) and Roy Wilkins. Behind Reuther is Vice-President Lyndon Johnson. (Three Lions/Getty Images)

In addition to congressional legislation, a major cultural shift is also credited to the march. According to The Washington Post, “While racial bigotry was not dead, it was no longer respectable…not something that could be openly proclaimed by Cabinet officers, corporate leaders, even presidents of the United States. It’s true shamefulness and cruelty became part of the national consciousness that day…”8

The legacy of the March on Washington could be summed in a word – progress. In the years that followed, it would be untrue to say racism, bigotry, and the like were eradicated from the steps of the national mall, but progress was made which can be seen, felt, and heard from every corner of the nation.

Today, Randolph’s closing words still ring true for peoples everywhere fighting for justice. “We are the first wave. When we leave, it will be to carry the … revolution home with us into every nook and cranny of the land, and we shall return again and again…in ever-growing numbers until total freedom is ours.”9

-

- 1 Haley, Alex, Anita J. Aboulafia, and Michael Kupka. The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Piscataway: Research and Education Association, 1996.

- 2 “An Oral History of the March on Washington.” Smithsonian.com. July 01, 2013. Accessed August 21, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/oral-history-march-washington-180953863/

- 3 History.com Staff. “March on Washington.” History.com. 2009. Accessed August 21, 2018. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/march-on-washington.

- 4 “An Oral History of the March on Washington.” Smithsonian.com. July 01, 2013. Accessed August 21, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/oral-history-march-washington-180953863/

- 5Id.

- 6 King, Rev. Marting Luther, Jr. “I Have a Dream.” Speech, March on Washington, Lincoln Memorial, Washington, D.C., August 23, 1963.

- 7 “An Oral History of the March on Washington.” Smithsonian.com. July 01, 2013. Accessed August 21, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/oral-history-march-washington-180953863/

- 8 Editorial Board. “The March on Washington: A Symbol, If Not a Turning Point.” The Washington Post. August 27, 2013. Accessed August 21, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-march-on-washington-a-symbol-if-not-a-turning-point/2013/08/27/c02bd7e4-0f40-11e3-bdf6-e4fc677d94a1_story.html?utm_term=.568fc9b3bbec

- 9 History.com Staff. “March on Washington.” History.com. 2009. Accessed August 21, 2018. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/march-on-washington.