By: TAYLOR KING

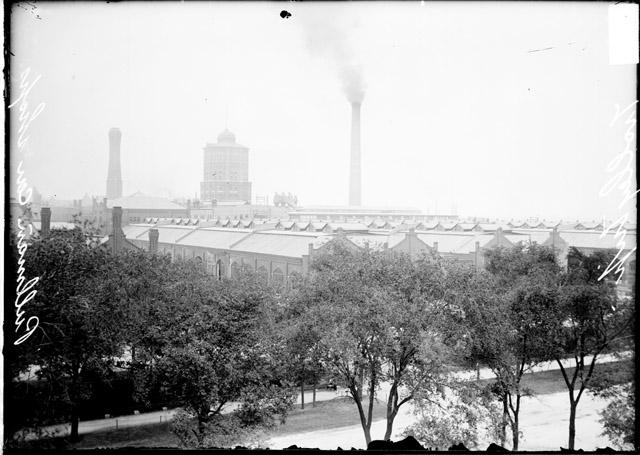

Puffs of smoke billow from a factory chimney in Pullman, Illinois, in 1893, filling the skyline with the hopes of progress. This Chicago suburb, nestled in the stretch of America now known for its rust and decay, had just begun to glisten with opportunity.

As the First Industrial Revolution swept across the country, a new class of citizens emerged — the middle class. Before this time, lower-class citizens had little to no opportunity to grow their wealth. Most work was self-sustaining, meaning families worked to provide for themselves and their immediate communities. However, with the introduction of mass production, work began to transform into a regional, national, and global marketplace.1

And with the creation of new industries came a now well-known issue—the commute.2 Work on the railways, in lumber yards, and in coal mines (unlike the traditional urban-community factories of their time) often existed far outside the city. However, commuting was often not a possibility for those in the middle class. As a result, owners of major manufacturing corporations needed a pragmatic solution for transporting their employees to work.

Company towns became the ideal solution. Towns were created next to the factory or work site. They offered everything citizens needed from grocery stores and schools to churches and parks. However, there was a catch. The employing company owned, operated, and governed the town, meaning it had absolute control over how, where, and when employees spent their income.

Although seemingly intended for the benefit of the middle class, the wealthiest in America designed the towns for the benefit of themselves. Their often paternalistic ideas of a proper, functioning society permeated the culture of the towns, leaving citizens with little choice and a one-size-fits-all approach to living.3 Pullman, Illinois, was one of those towns.

George M. Pullman first developed the town in 1879 to house workers for his railcar production factory, the Pullman Palace Car Company. He didn’t require his workers to live in the town, but he made a very compelling offer. While he charged slightly higher rent rates compared to what was typical for the Chicago area, the living conditions were significantly improved.

During the Industrial Revolution, workers often lived in slum-like conditions with five to nine people to a single room.4 Pullman offered an alternative. His housing provided tenants with access to gas, water, sanitary facilities, and big backyards. The monthly rent included regular maintenance — even garbage pickup!5 A utopia of its time, the town was a dream come true for many.

In 1893, the dream began to disintegrate. Two of the country’s largest employers – the National Cordage Company and the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad – filed for bankruptcy, causing the entire United States’ economy to free fall.6 Stock prices plummeted causing panic across the nation. The crisis eventually forced the closure of 500 banks and the failure of more than 15,000 businesses, leading to massive amounts of unemployment.7

The Pullman Company was not immune to the effects. Determined not to join the growing list of failed companies, Pullman decided to cut already-low wages by around 25 percent, devastating his workforce but safeguarding his company. When monthly rent was due from those living in Pullman’s housing, rent prices did not budge, leaving his tenants unable to pay their bills. The prosperous dream town quickly became a nightmare, spiraling the employees into poverty with each paycheck.

Unionizing was illegal in the town of Pullman, blocking employees’ ability to speak into their treatment.8 In fact, Pullman placed spies around the town to keep tabs on any attempts to organize.9 As the crisis worsened, workers found they had little ability to save themselves. Desperate, a small group of 46 employees met secretly with Pullman on two occasions in hopes of striking deal. Despite their pleading, Pullman continued to refuse compromise, even firing the workers who expressed their grievances.10

In the summer of 1894, 35 percent of Pullman workers were secretly represented by the American Railway Union (ARU), a union that successfully led a strike against the Great Northern Railway Company just months before.11 Although the Great Northern Railway Company’s strike proved successful, partnering with the ARU would be much riskier for the Pullman workers. Since union-backed arbitration was illegal, partnering with the ARU in any way was very risky.

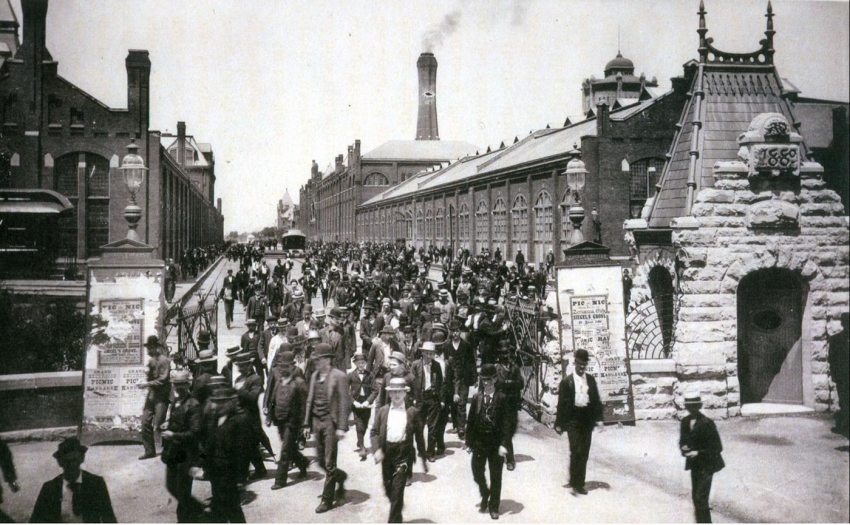

In 2019, workers across the U.S. are proving that the legacy of the Great Pullman strike is still alive today. (Wikipedia Commons)

On May 11, 1894, the Pullman workers decided to take the risk. Marching together, they walked off the job with the hope the ARU would find a way to advocate on their behalf. In June, the ARU met in Chicago for their first annual convention. By this time, sympathy for the Pullman workers had spread throughout the region. The ARU did not want to turn a blind eye, but what could they do?

On June 26, the ARU decided to submit an arbitration request to the Pullman Company. The request contained a clear consequence. If no solution could be found, the ARU would implement a plan of action, which included a boycott on Pullman Company Cars and removal of Pullman Cars from rail systems throughout the United States.12

Despite the ARU’s attempt, the Pullman Company refused the request. As a result, the ARU retaliated exactly as promised. The next day, 5,000 railroad workers left their jobs, preventing 15 local railroads from operating on schedule.13 By June 30, 1894, the number of striking rail workers reached 125,000, causing the American rail system to nearly grind to a halt.14 The plan was working. The strikers had instituted the first national strike in United States’ history.15

However, with each day of unemployment, the desperation of the striking workers grew. Walk-offs gave way to more hostile methods of expression. Riots and mobs began pillaging and burning railcars across the country.16 The resulting pandemonium pushed the strike to the national stage. President Grover Cleveland decided to intervene.

At the beginning of July, President Cleveland instituted an injunction, calling the strike a federal crime. He sent 12,000 federal troops to break up the conflict, marking the first time in history federal armed forces were sent to intervene in this type of dispute.17 When the troops arrived in Chicago on July 4, violence erupted in the streets, killing 26 civilians in one day.18

At the beginning of July, President Cleveland instituted an injunction, calling the strike a federal crime. He sent 12,000 federal troops to break up the conflict, marking the first time in history federal armed forces were sent to intervene in this type of dispute.17 When the troops arrived in Chicago on July 4, violence erupted in the streets, killing 26 civilians in one day.18

The conflict continued to intensify. Over the next two days, 6,000 federal and state troops, along with more than 3,000 police and 5,000 deputy marshals, moved into the city to quell the crowds. They remained unsuccessful. The strike finally began to dwindle when the General Managers’ Association began hiring non-union workers allowing normal rail schedules to resume.19

On July 20, 1894, the strike ended. Less than two weeks later, the Pullman Company reopened their doors, agreeing to rehire the striking workers on one condition — they would sign a pledge to never join a union. After more than two months of striking, the Pullman workers, with no better options, chose to return to the company town they spent months fighting against.

It took decades for the strikers that made history to see the fruits of their labor, but they did come. The leader of the ACU (and main figurehead of the Pullman Strike), Eugene V. Debs, continued to be the voice of the middle-class workers. He ran for president five times between 1900 and 1920, pushing for workers’ rights. Although he lost the elections, both Republicans and Democrats began to embrace the progressive reforms advocated by Debs such as anti-trust and child labor laws, minimum wages, and the eight-hour workday.

July 20, 2019, marks 125 years since the Pullman Strike ended. Today, we remember the losses that paved the way for the future; we acknowledge the setbacks that led to the victories; and we revere the sacrifices that laid the ground for workers’ rights for all generations to come.

- 1 “Industrial Revolution.” Wikipedia. July 09, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_Revolution.

- 2 “Industrial Revolution.” Wikipedia. July 09, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_Revolution#Labour_conditions.

- 3 “Company Towns: 1880s to 1935.” Social Welfare History Project. March 12, 2018. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/programs/housing/company-towns-1890s-to-1935/.

- 4 “Working and Living Conditions.” The Industrial Revolution. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://firstindustrialrevolution.weebly.com/working-and-living-conditions.html.

- 5 Historic Pullman Foundation. Accessed July 19, 2019. http://www.pullmanil.org/town.htm.

- 6 “Panic of 1893.” Panic of 1893 – Ohio History Central. Accessed July 19, 2019. http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Panic_of_1893.

- 7 “Panic of 1893.” Wikipedia. July 02, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panic_of_1893.

- 8 125 Years After the Pullman Uprising, We Could Be on the Verge of Another Sympathy Strike Wave. Accessed July 19, 2019. http://inthesetimes.com/working/entry/21936/pullman-strike-sympathy-sara-nelson-chicago-labor/.

- 9 Id.

- 10 Urofsky, Melvin I. “Pullman Strike.” Encyclopædia Britannica. July 18, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/event/Pullman-Strike.

- 11 125 Years After the Pullman Uprising, We Could Be on the Verge of Another Sympathy Strike Wave. Accessed July 19, 2019. http://inthesetimes.com/working/entry/21936/pullman-strike-sympathy-sara-nelson-chicago-labor/.

- 12 Urofsky, Melvin I. “Pullman Strike.” Encyclopædia Britannica. July 18, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/event/Pullman-Strike.

- 13 Urofsky, Melvin I. “Pullman Strike.” Encyclopædia Britannica. July 18, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/event/Pullman-Strike/The-injunction.

- 14 Id.

- 15 “Company Towns: 1880s to 1935.” Social Welfare History Project. March 12, 2018. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/programs/housing/company-towns-1890s-to-1935/.

- 16 Desk, News. “The Origins of Labor Day.” PBS. September 03, 2001. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/business-july-dec01-labor_day_9-2.

- 17 McNamara, Robert. “Federal Troops Were Sent to Break the 1894 Pullman Strike.” ThoughtCo. January 23, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://www.thoughtco.com/the-pullman-strike-of-1894-1773900.

- 18 Id.

- 19 Urofsky, Melvin I. “Pullman Strike.” Encyclopædia Britannica. July 18, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/event/Pullman-Strike/The-injunction.