By: MOLLY WICKER

On February 1, 1960, four black college students sat down at a “whites-only” lunch counter at Woolworth’s in Greensboro, N.C. and refused to leave after being denied service. Additional students joined them over the following weeks and months, and sit-in protests spread through North Carolina to other states in the South. Though many of the protestors were arrested for trespassing, disorderly conduct, or disturbing the peace, their actions made an immediate and lasting impact, forcing Woolworth’s and other establishments to change their segregationist policies.

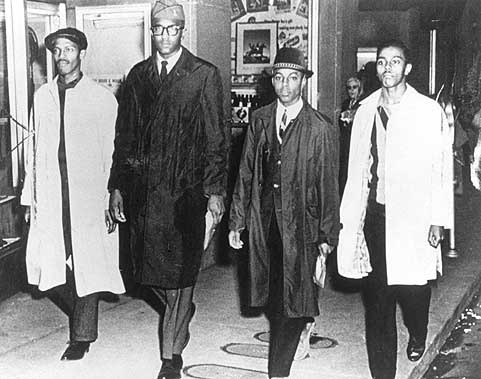

The first sit-in was staged by Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, David Richmond, and Ezell Blair, who were all students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College. They were influenced by the non-violent protest techniques practiced by Mohandas Gandhi, as well as the Freedom Rides organized by the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) in 1947, in which interracial activists rode across the South in buses to test a recent Supreme Court decision banning segregation in interstate bus travel.

The Greensboro Four, as they became known, had also been spurred to action by the brutal murder in 1955 of a young black boy, Emmett Till, who had allegedly whistled at a white woman in a Mississippi store.

Blair, Richmond, McCain, and McNeil planned their protest carefully and enlisted the help of a local white businessman, Ralph Johns, to put their plan into action. On February 1, 1960, the four students sat down at the lunch counter at the Woolworth’s in downtown Greensboro, where the official policy was to refuse service to anyone but white. Denied service, the four young men refused to give up their seats.

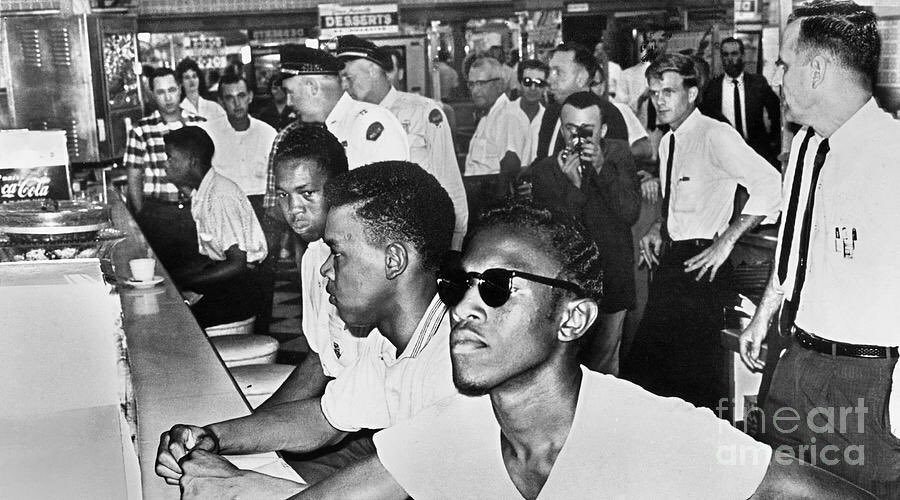

Police arrived on the scene but were unable to take action due to the lack of provocation. By that time, Johns had already alerted the local media. By that time, Johns had already alerted the local media, who had arrived in full force to cover the events on television. The Greensboro Four stayed put until the store closed, then returned the next day with more students from local colleges.

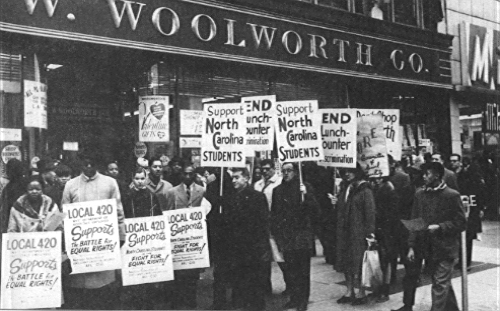

By February 5, some 300 students had joined the protest at Woolworth’s, paralyzing the lunch counter and other local businesses. Heavy television coverage of the Greensboro sit-ins sparked a sit-in movement that spread quickly to college towns throughout the South and into the North, as young blacks and whites joined in various forms of peaceful protest against segregation in libraries, beaches, hotels, and other establishments.

The New York Times reported on the growing movement in its February 15 edition, noting that “the demonstrations were generally dismissed at first as another college fad . . . this opinion lost adherents, however, as the movement spread from North Carolina to Virginia, Florida, South Carolina, and Tennessee and involved fifteen cities. Some whites wrote off the episode as the work of ‘outsider agitators.’ But even they conceded that the seeds of dissent had fallen in fertile soil.”

Segregated lunch counters were common in the South because of numerous Jim Crow laws, which also kept public buildings and sites like libraries, parks, theaters, swimming pools, and water fountains segregated. The sit-in protests drew public attention to these injustices through non-violent civil disobedience.

By the end of March, the movement had spread to 55 cities in 13 states. Though many were arrested for trespassing, disorderly conduct or disturbing the peace, national media coverage of the sit-ins brought increasing attention to the civil rights movement.

Reactions to the sit-in protesters varied by restaurant. In many places, groups of white men gathered around the protestors to heckle them and use occasional violence. “In a few cases the Negroes were elbowed, jostled, and shoved. Itching powder was sprinkled on them and they were spattered with eggs,” The Times reported. “At Rock Hill, S.C., a Negro youth was knocked from a stool by a white beside whom he sat. A bottle of ammonia was hurled through the door of a drug store there. The fumes brought tears to the eyes of the demonstrators.” Many managers closed their counters rather than deal with the protests.

By 1960, dining facilities across the South were being integrated by the summer of 1960. At the end of July, when many local college students were on summer vacation, the Greensboro Woolworth’s quietly integrated its lunch counter. Four black Woolworth’s employees – Geneva Tisdale, Susie Morrison, Anetha Jones and Charles Best – were the first to be served.

The sit-ins helped to attract young people to the civil rights movement and create new leaders and organizations. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which would become an influential organization in the movement, was founded at a conference of sit-in leaders.

The sit-in protests were successful in integrating lunch counters, including the Greensboro Woolworth’s, which gave in to the public protestors in July 1960. Four years later, segregation of public place was made illegal when Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.