Rafael* was mostly excited to be on the plane headed back to the United States from the Dominican Republic. He had spent the off-season with his family, having plenty of quality time with his teenage sons and especially his father, who was getting on in years. He knew a friendly game of catch would not be possible with his father for much longer. Getting back to his team in the States, Rafael knew there would be a reunion with many of those he was with last year. But he was not rejoining a baseball team, he was returning to seasonal farm work in central Minnesota.

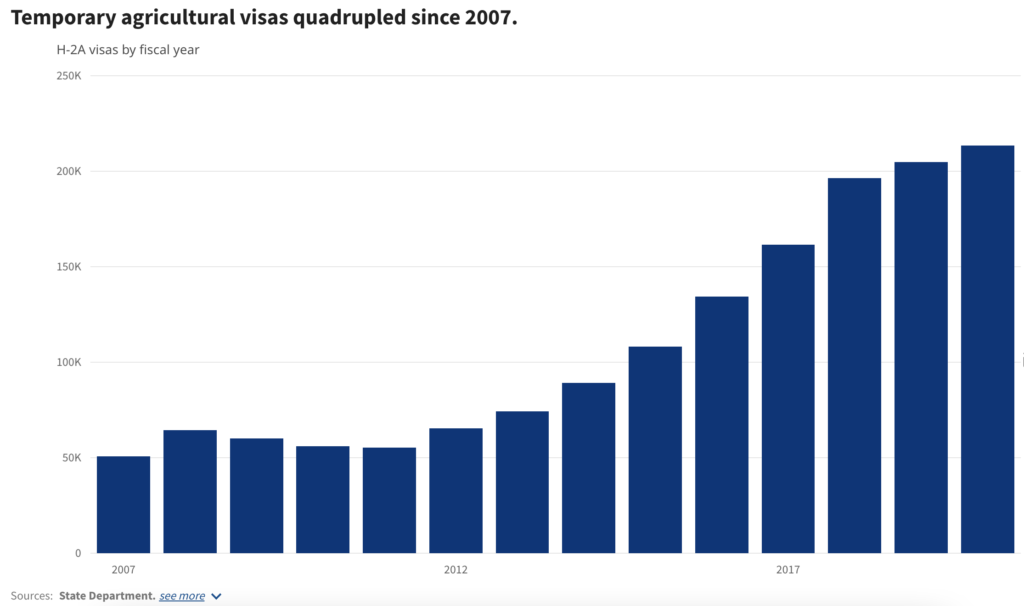

Rural America has seen a steady population loss for generations. Young Americans often expect college educations, high-paying jobs, and the finer things in life, all goals that don’t necessarily align with the physical labor needed for a life in agriculture. The farm industry has been increasingly dependent upon foreign workers to get products to our dinner tables. Some may assume all foreign farmworkers are “illegal aliens” sneaking across the southern border, but in reality, hundreds of thousands of people are granted valid work visas specifically for seasonal agriculture work in the United States. Through a process overseen by the Department of Labor, but with input from other government sectors (the Department of Agriculture, Department of State, and Department of Homeland Security), U.S. farms can be certified as places of employment for temporary workers. And for the most part, the system works: crops are planted and harvested, workers receive payment and experience working in the U.S., and then workers return to their home countries. In many cases, the money earned during one agricultural season here in America can sustain them and their families for the rest of the year back home.

Of course there are some outliers, those who take advantage of the system: absconders who never show up to the job site at all, some who enter into false marriages for the citizenship benefits, and others who fade into U.S. society once their farm work has ended. Most people are not trying to game the system; it is legal to change your visa status in order to attend school, or if a foreign visitor does find love and seeks to marry a U.S. citizen through legal, official channels.

What about when the American employer is the outlier? What about instances where employers knowingly cheat their foreign workers? For workers like Rafael, many get used to having to pay an annual fee to someone posing as a recruiter and later having additional deductions taken out of their paychecks. Employers frequently provide housing legally to their foreign workers, but it is not legal to then charge exorbitant fees for substandard housing without functioning heat or air conditioning, worn or damaged furniture, and inadequate plumbing and sewage. Necessary equipment like gloves, boots, or crop-specific tools are usually provided by farm owners, but shadier practices like billing workers for replacement tools or not providing safe and sanitary conditions further indicates an exploitive environment.

All of this means workers like Rafael frequently earn far less than they are expecting. Yet many return to the same farm each year. While Rafael no longer goes through the recruiting process, each year he still pays $375 to a recruiter he met years ago when he was first applying to work in the United States. So why does Rafael, and many more workers like him, return to the same job year in and year out when they know they will be charged illegal fees, always reducing their pay? For most, the answer is clear: they can still earn more in the United States than in their home country.

Does the farm owner know his workers are getting scammed? Sometimes not, if the fraud starts away from the worksite. Small American farms rely on word of mouth or outside help in attracting workers to farms, so the farm owner might not be involved in recruiting, hiring, and the coordination for international travel required to bring foreign workers to their farm. But, in aggregious cases like Rafael’s, the business owners were complicit with recruiters, headhunters, and other middlemen in facilitating visa fraud to keep a steady flow of workers on the farm.

Some recruiters are seemingly helpful and supportive during the initial phases of hiring workers and placement at worksites. But other recruiters coerce and exploit workers, both in the hiring and working phases. A case in Ohio revealed men and teenage boys from Central America were being recruited to work in agricultural industries, specifically egg farms. Traffickers exacted a very high recruiting fee: fifteen thousand dollars. If a prospective worker could not afford that up-front fee, the recruiter told them to use the deed to their family property for collateral, promising they would make so much money once in the United States that they could easily pay off their recruiting fees. However, tacked-on fees at the worksite added up and their employers never seemed to leave enough take home pay to pay off the debt the men had incurred just in getting to the United States, resulting in a form of trafficking, debt bondage.

When a laborer knows he or she is being cheated, it may not be easy to complain to the boss or ask for a raise. Aside from language barriers, traffickers frequently withhold legal documents such as passports or ID cards, and many foreign workers do not fully understand their legal rights. In many forced labor cases the work can be excruciating, frequently more than eight hours per day, more than five days per week. If a worker complains, traffickers might threaten their victims with some form of harm, real or implied, occasionally directed at distant family members. In the case involving workers at the Ohio egg farm, traffickers threatened to harm family members in their home cities in Central America. The fear was real as the laborers realized the recruiters knew exactly where their families lived. The implied harm that might come to their family members back home was enough of a coercive element to compel them to keep working even under deplorable conditions. Often, methods of coercion do not involve physical restraint or violence. In 2020, 59% of coercive tactics found in federal prosecutions were nonphysical, like those used on this farm.

While labor trafficking could manifest like these examples, there may be so many variables associated with forced labor, depending upon the region of the country, the type of crop produced, and the amount of labor required to care for the crop. But essentially, a case of human trafficking related to farm laborers needs three elements: force, fraud, and coercion, all of which were realities for Rafael and his co-workers. That is, until an anonymous tipster shared concerns with the U.S. Department of Labor. The allegations were investigated by a task force of multiple Federal and State of Minnesota agencies, all working together to ensure Federal prosecutors in Minneapolis would hold the traffickers accountable in court. A key factor in the success of the case, and a growing number like it, was the specialized support provided to victims by social service advocates and agencies. Ensuring the victims’ needs are met, from basic needs like food and shelter, to more complex and lengthy issues such as medical care and legal assistance, is frequently the crucial key to a successful prosecution. A trauma-informed, victim-centered approach to fighting human trafficking encourages survivors to participate by giving statements and testimony only as they feel secure facing their alleged traffickers. The three traffickers in Rafael’s case were sentenced to Federal prison terms for their crimes.

Last week, we celebrated National Farm Workers Day, a chance for all of us as consumers to fully appreciate those who ensure we have food for our families, and also a chance to celebrate the history of agriculture in the United States. The American Dream of seeking new opportunities to improve livelihoods is echoed in many of the foreign agricultural workers laboring in farms across the country.

So tonight as I consider a steak and potatoes dinner, I will thank the American Farmer and all farmworkers who make this meal possible from cattle feedlots outside Friend, Nebraska to the garlic fields surrounding Gilroy, California, and the potato farms around Presque Isle, Maine.

But I will also be mindful that this industry can be exploited by trafficking. Farm work is labor intensive and difficult. All farm workers across America deserve to be paid fairly for their labor and have safe work conditions, whether they are U.S. citizens or visa-holding foreign workers helping to support our food system.

If you would like to report ongoing instances of human trafficking, especially in the agriculture industry, please contact the National Human Trafficking Hotline at 1-888-373-7888. If you know of someone in immediate danger, please call 911. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/report-trafficking

*pseudonym