By: Cj MURPHY

On October 19, 1781, British troops surrendered to the American Continental Army in Yorktown, Virginia. This battle informally marked the end of the American Revolutionary War and answered the colonists’ call for freedom from the British Crown. However, this did not mean freedom for everyone.

The cause of liberty for enslaved African Americans was largely renounced by the colonists and accordingly written out of the history of the Revolutionary War. However, the role of slaves in the war’s narrative is undeniable and serves as a reminder of the true cost of freedom.

Role of slaves in the early years of revolution

When George Washington took command of the Continental Army in 1775, he ordered that no African Americans could enlist.1 This command stemmed from the fear that arming slaves could spur a slave rebellion.

British Lord Dunmore, on the other hand, capitalized on this fear by issuing a proclamation that all rebel-owned slaves who joined British forces would be granted freedom.2 Within a month of the proclamation, more than 300 slaves had joined the British Army.3 By the war’s end, more than 5,000 slaves joined the British forces — a testament to the lengths enslaved people would go for a chance at freedom.4

Upon enlistment in the British Army, African American slaves were put into the Ethiopian Regiment – the words “Liberty to Slaves” embroidered on their uniform sashes5. They built infrastructure, engaged in trades like shoemaking and carpentry, and performed services like cooking and nursing.6

Later in the war, the British transitioned runaway slaves into combat roles within the army7. General Henry Clinton organized one of the first all-black regiments, called “the Black Pioneers.”8 Among its ranks included Harry Washington, an escaped slave of George Washington who rose to become a corporal9.

Inclusion of slaves in the Continental Army

By 1778, Washington had recognized the growing strength of the British Army, crediting their victories to their recruitment of slaves.10 So when Rhode Island Governor James Mitchell Varnum wrote to Washington saying he wanted to enlist slaves in the military, Washington agreed. Rhode Island formed an all-black regiment of 88 men, who quickly became “the most neatly dressed, the best under arms and the most precise in maneuvers,” according to one of Washington’s advisors.11

The Rhode Island regiment was unique among black regiments because the slaves were guaranteed freedom at the end of their service.12 This benefit was conferred on the Rhode Island regiment when the Rhode Island State Assembly promised to compensate their former owners for the cost of their forsaken property13. This differed from the approach taken in other areas of the colonies, as the overwhelming majority of slaves who fought for the Continental Army remained the property of their owners.14

Gradually, the recruitment of slaves grew throughout the colonies. By the time of the Battle of Yorktown, black units comprised one quarter of the American forces.15

The Battle of Yorktown

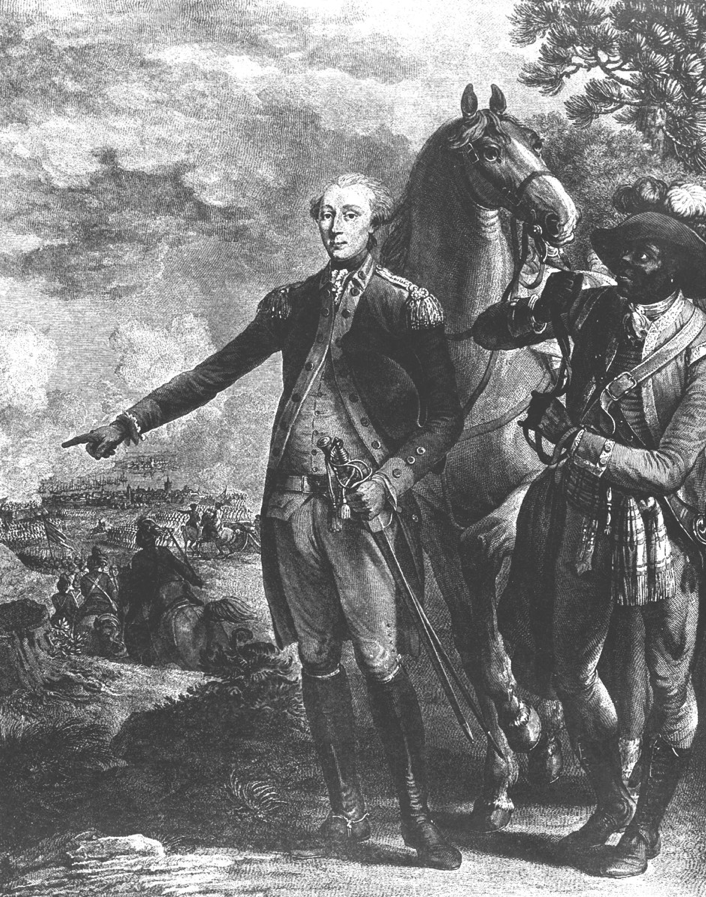

Washington and Rochambeau strategizing during the Yorktown Campaign

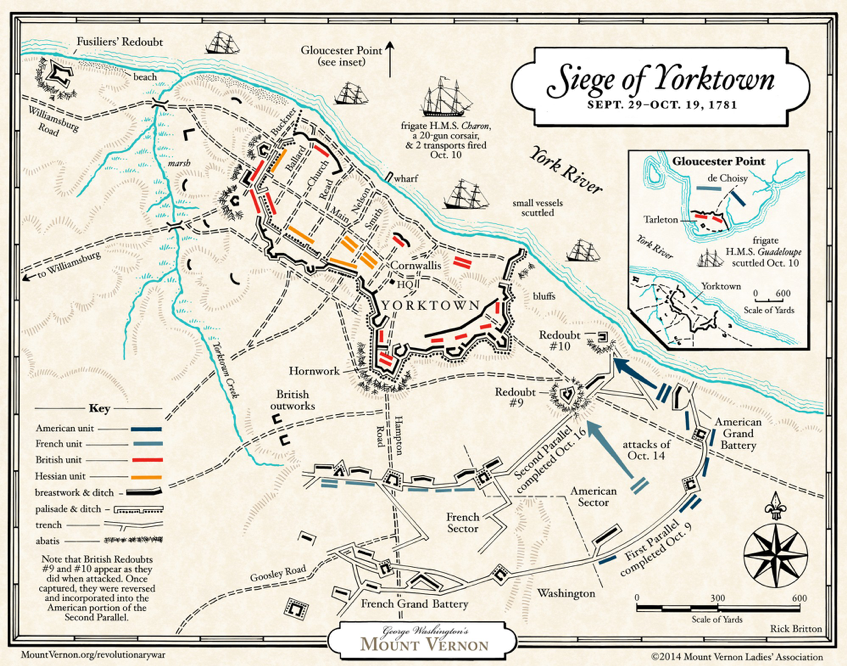

On August 1, 1781, British General Lord Charles Cornwallis occupied Yorktown, Virginia, planning to use the port city as a base to resupply his troops.16 Washington used this location to his advantage and planned to surround the British troops by land and sea. He ordered Marquis de Lafayette to circle Cornwallis’s forces and block an escape by land. Washington then instructed Comte de Grasse to erect a blockade of the port using his fleet of French ships.17 This dual approach left Cornwallis without reinforcements or an exit strategy.

After cornering the British troops, the Continental Army bombarded their enemy with artillery for over a week.18 Slaves fighting for the patriot cause engaged in combat and manned American siege lines, helping troops progress toward the British.19 Slaves in the British Army were also sent into battle, especially those who were ill with smallpox.20 The British hoped that driving these troops toward the Continental Army would spread smallpox and wipe out some of their enemy’s numbers.21

After weeks of fighting and seeing little hope for success, the British forces surrendered to the Continental Army. This action effectively ended the Revolutionary War and signified a victory for American troops.

James Armistead: The key to American triumph at Yorktown

James Armistead and Marquis de Lafayette

A key player in securing the American victory at Yorktown was slave James Armistead. Born into slavery in 1748, Armistead enlisted in the war with the permission of his master.22 Serving under Marquis de Lafayette, Armistead was instructed to spy on the British Army by posing as a runaway slave who wanted to fight for the Crown.23 After gaining the trust of Cornwallis and other high ranking British officers, Armistead was assigned to spy on the Continental troops.24 This role gave Armistead the ability to travel freely between British and Continental forces. This position also meant that if Armistead was found out by the British, he would be hanged.25

Utilizing his access to military intelligence, Armistead provided information about British troop movements to secure an American victory at the Battle of Yorktown.26 His information allowed American forces to trap the British on the Yorktown peninsula and create a naval blockade to prevent British reinforcements from reaching shore.27

Despite his valiant service in the Revolutionary War, Armistead was returned to slavery once the fighting concluded.28 Given that only an act of the legislature could free a slave in Virginia, Armistead’s owner petitioned the Virginia legislature for his freedom in 1784, asking for “that liberty which is so dear to all mankind.”29 However, the petition failed in the legislature, as Virginia law only provided an avenue to freedom for slaves serving in the war as soldiers — not spies.30

Two years later, Armistead’s owner again petitioned for his freedom, this time attaching a personal recommendation from Marquis de Lafayette. Armistead’s owner implored the legislature to grant him “that Freedom, which he flatters himself he has in some degree contributed to establish.”31 That petition succeeded, finally emancipating Armistead. Lafayette personally attended the manumission of Armistead, who took “Lafayette” as his last name upon receiving his freedom.32

John Trumbull’s rendition of the surrender of the British forces at Yorktown.

Slaves and the aftermath of the Revolution

Like Armistead, slaves were in a state of deep insecurity concerning their prospects of freedom at the conclusion of the Revolutionary War. As the British and Americans negotiated a peace treaty, one critical term was the return of American property, including runaway slaves.33 Former British soldier and runaway slave Boston King recalled:

“[P]eace was restored between America and Great Britain, which diffused universal joy among all parties, except us, who had escaped from slavery, and taken refuge in the English army; for a report prevailed at New York, that all the slaves…were to be delivered up to their masters…. This dreadful rumour filled us all with inexpressible anguish and terror, especially when we saw our old masters coming…and seizing upon their slaves in the streets of New York, or even dragging them out of their beds.”34

Those who thought they were trading military service for eventual freedom now saw that dream vanish. They were once again property.

However, British commander Sir Guy Carleton refused to abandon African-American Loyalists to their fate as slaves.35 Carleton insisted he would honor the previous proclamations of freedom because to do otherwise would be a “dishonorable Violation of the public Faith.”36 Accordingly, Carleton vowed to pay restitution to American slave owners and free those that fought for the British Army.37

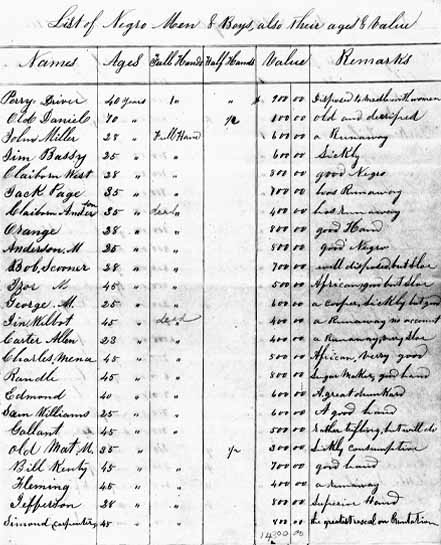

Book of Negroes, PBS

Within a year, the British had compiled a list of thousands of former slaves who enlisted in the British army in hopes of freedom, called the Book of Negroes.38 Carleton issued these men, women, and children certificates of freedom and ensured they were able to board military ships leaving America. These former slaves eventually settled in Nova Scotia, Sierra Leone, Jamaica, and Britain.39

Working toward freedom for all

The Battle of Yorktown represented freedom for colonists across America, but it also represented the inhumanity of slavery throughout the United States. Though slaves were excluded from the “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness” referenced in the Declaration of Independence, they need not be excluded from the history of the Revolution. On this day in history, be mindful to acknowledge slavery and what we can do to work toward freedom for all.

-

- 1 https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2narr4.html

- 2 Id.

- 3 Id.

- 4 https://www.history.com/news/the-ex-slaves-who-fought-with-the-british

- 5 Id.

- 6 Id.

- 7 Id.

- 8 Id.

- 9 Id.

- 10 https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-secret-black-history-of-the-revolution

- 11 Id.

- 12 https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/african-americans-and-war-independence

- 13 Id.

- 14 http://www.history.org/foundation/journal/autumn07/slaves.cfm

- 15 https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-secret-black-history-of-the-revolution

- 16 https://www.nps.gov/york/learn/historyculture/eventstoyorktown.htm

- 17 https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/yorktown-campaign/

- 18 https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/yorktown

- 19 https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/african-americans-and-war-independence

- 20 http://www.history.org/foundation/journal/autumn07/slaves.cfm

- 21 Id.

- 22 https://www.biography.com/people/james-armistead-537566

- 23 Id.

- 24 Id.

- 25 http://www.historynet.com/the-slave-who-spied-james-armisteads-role-in-revolutionary-war.htm

- 26 https://www.biography.com/people/james-armistead-537566

- 27 Id.

- 28 Id.

- 29 http://www.historynet.com/the-slave-who-spied-james-armisteads-role-in-revolutionary-war.htm

- 30 Id.

- 31 Id.

- 32 https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/african-americans-and-war-independence

- 33 https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2narr4.html

- 34 Id.

- 35Id.

- 36 https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h58.html

- 37 Id.

- 38 Id.

- 39 https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2narr4.html