By: TAYLOR KING

In 1870’s America, the civil war is over. The state of Mississippi elected the first black American congressman to represent the state’s interests in the federal government. Congress passed the 15th amendment, making it illegal to bar a citizen from voting on the basis of their skin color. And, for the first time, black citizens are allowed to own property anywhere in the United States.

Black Americans rejoiced in this newfound freedom, and yet, as the country settled into its “new normal,” it seemed the bondage of the past made way for the bondage of the future. A new hat with the same shape.

At the same time, the railcar business was beginning to take off due to the success and ease of rail travel. Budding entrepreneurs quickly took advantage of the booming market of the industrial revolution and the labor opportunities the new black workforce provided. The Pullman Palace Car Company was no exception.

George M. Pullman founded the company eight years prior in 1862. While railcar companies across the country focused on efficiency and necessity, Pullman saw a window of opportunity in the luxury car market. Designing railcars for the wealthiest of Americans, he introduced a new standard for rail travel—sleeping cars.1

While the cars enjoyed early popularity, the real success came after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in 1865. The government chose a luxury Pullman railcar to house Lincoln during the final leg of his funeral procession, blasting the eponymous sleeping car into the national spotlight.2

With this invention came a need for labor — and not only for the cars’ manufacturing and design. The Pullman company staffed each car with a number of porters, who, until almost 100 years later, were exclusively black. Porters were responsible for greeting passengers, transporting luggage, making the beds, shining shoes, and providing drinks. In other words, a porter’s job was to ensure a passenger was left wanting for nothing.3

The Pullman Porter occupation was highly regarded among the African American community. The job offered a regular income, limited physical labor, and an opportunity to travel across the country.4 While these positions were a significant improvement from previous decades of enslavement, the positions lacked equal pay and treatment.

The Pullman Company expected porters to work 400 hours a month (roughly 60 hours per week) — sometimes in 20-hour stretches.5The Pullman Rule Book allowed porters to have three hours of sleep the first night the car was in tow and none for the second night.6 Porters paid for their own meals and purchased their own uniforms.7 When porters stepped onto the railcar, they were required to respond to the nickname, “George,” after the company’s owner, whether intentionally or not stripping the porters of their own identity.

In 1894, the successful giant began to lose its footing when the company’s white factory workers arranged a national strike. Struggling with below poverty-level wages due to the stock market’s free fall and unfair rent requirements from the Pullman Company, the white workforce decided to organize with the American Railway Union to argue for better pay.8

When the white factory workers walked out, Pullman required black porters to replace them.9Throughout the chaos of strike, the voices and hardships of the black Pullman employees were all but lost. In July 1894, the white strikers returned to work, their heads hanging in defeat, and black porters returned to their posts as railcar servants.

For the next 30 years, black employees saw very little change in the working conditions at the Pullman Company. By 1925, black workers were fed up with low wages and unfair treatment, so they turned to civil rights activists A. Phillip Randolph and Milton P. Webster for help. Although reluctant at first, Randolph eventually agreed to publish their demands in a socialist magazine, The Messenger. In the article, porters asked for a living wage instead of the $810 per year wage10 (equivalent to $11,875 today)11 they were earning. They pleaded for a 240-hour work month and the ability to get four to six hours of sleep each night. The articles received a wide range of support.12

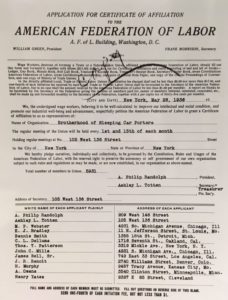

BSCP charter application, New York, May 26, 1936. AFL-CIO Photographic Print Collection (RG96-001)

Together, the disgruntled porters, Randolph, and Webster unionized as the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) on August 25, 1925. The federal government immediately refused the BSCP’s demand for recognition, and the Pullman Company refused to offer the porter’s a living wage. Instead, the company, almost certainly empowered by their win over the white workers’ strike 30 years prior, fired dozens of black workers who had helped form the union.13

Over the next 10 years, the Pullman company deployed various tactics – from spies and intimidation to propaganda spread among their own African American community – to dissuade the union.14 Relentless, BSCP argued for their rights against the trifecta of powerful decision-makers: the Pullman Company, the American Federation of Labor (AFL), and the majority pro-Pullman black community.15

Despite its charismatic and unwavering leadership, the union could not enroll a majority of porters.16 Randolph used his newspaper, The Messenger, to convince his readership of the union’s importance. Calling the Pullman Company, “a subtle recapitulation of the master-slave relationship,” he struck a chord within the black community.17

Then, in 1935, the unrelenting Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters gathered at the negotiating table in Harlem, New York, with the AFL and the Pullman Company. There, for the first time in history, a black union was recognized as legitimate, and their voices were heard. After two years of negotiations, their demands were met, and Pullman porters were given a living wage.

The BSCP’s influence, including on Randolph himself, is recognized today as a major catalyst in the Civil Rights movement. On this day in history, we recognize the tenacity of the BSCP and their fight for equality. Their victory should consistently serve as a reminder for all oppressed communities to endure, against all odds, for the right to be heard and the right to flourish.

- 1 Stamp, Jimmy. “Traveling in Style and Comfort: The Pullman Sleeping Car.” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, December 11, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/traveling-style-and-comfort-pullman-sleeping-car-180949300/.

- 2 Id.

- 3 “Pullman Porter.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, August 23, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pullman_porter.

- 4 “Pullman Porters, The: From Servitude to Civil Rights.” WTTW. Accessed August 25, 2019. https://interactive.wttw.com/a/chicago-stories-pullman-porters.

- 5 Id.

- 6 “Gershon, Livia. “The Historic Achievement of the Pullman Porter’s Union.” JSTOR, February 1, 2016. https://daily.jstor.org/historic-achievement-pullman-porters-union/.

- 7 Pullman Porters, The: From Servitude to Civil Rights.” WTTW. Accessed August 25, 2019. https://interactive.wttw.com/a/chicago-stories-pullman-porters.

- 8 King, Taylor. “On This Day in History: The Pullman Strike Ended.” Trafficking Matters, July 25, 2019. https://www.traffickingmatters.com/on-this-day-in-history-the-pullman-strike-ended/.

- 9 “Gershon, Livia. “The Historic Achievement of the Pullman Porter’s Union.” JSTOR, February 1, 2016. https://daily.jstor.org/historic-achievement-pullman-porters-union/.

- 10 “Pullman Porters, The: From Servitude to Civil Rights.” WTTW. Accessed August 25, 2019. https://interactive.wttw.com/a/chicago-stories-pullman-porters.

- 11 “Inflation Rate between 1925-2019: Inflation Calculator.” $810 in 1925 → 2019 | Inflation Calculator. Accessed August 25, 2019. http://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1925?amount=810.

- 12 Gershon, Livia. “The Historic Achievement of the Pullman Porter’s Union.” JSTOR, February 1, 2016. https://daily.jstor.org/historic-achievement-pullman-porters-union/.

- 13 Id.

- 14 Woodward, Laurie. “Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed August 25, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Brotherhood-of-Sleeping-Car-Porters.

- 15 Salter, Daren. “Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (1925-1978).” BlackPast, August 8, 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/brotherhood-sleeping-car-porters-1925-1978/.

- 16 Id.

- 17 Id.